Our Icons of the West series looks at the making of America’s original cowboy artist Charles M. Russell.

Written by Jenn Thornton

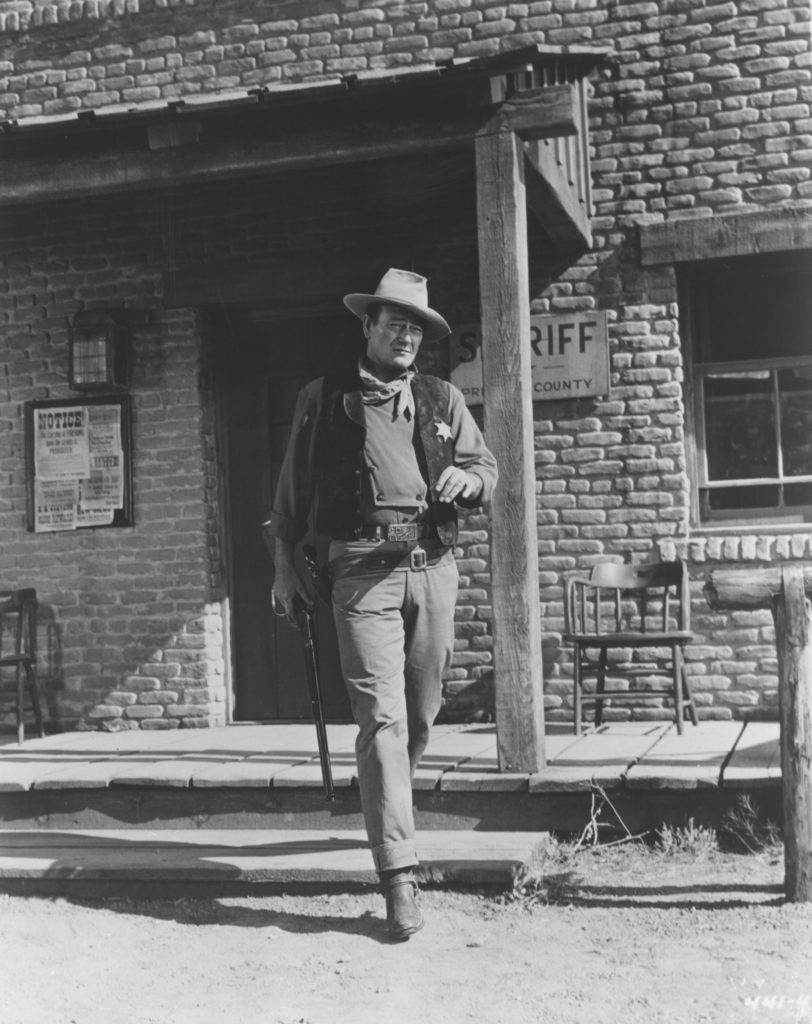

When John Wayne strode onto the film set of the beloved classic Rio Bravo (1959), he looked every bit the part of Sheriff John T. Chance who takes a stand against the bad guys with a ragtag band of deputies. The film reunited Wayne with both Howard Hawks, his director on Red River (1948), and cinematographer Russell Harlan, who modeled the look of Rio Bravo on the frontier paintings of another more famous Russell—Western art icon Charles M. Russell.

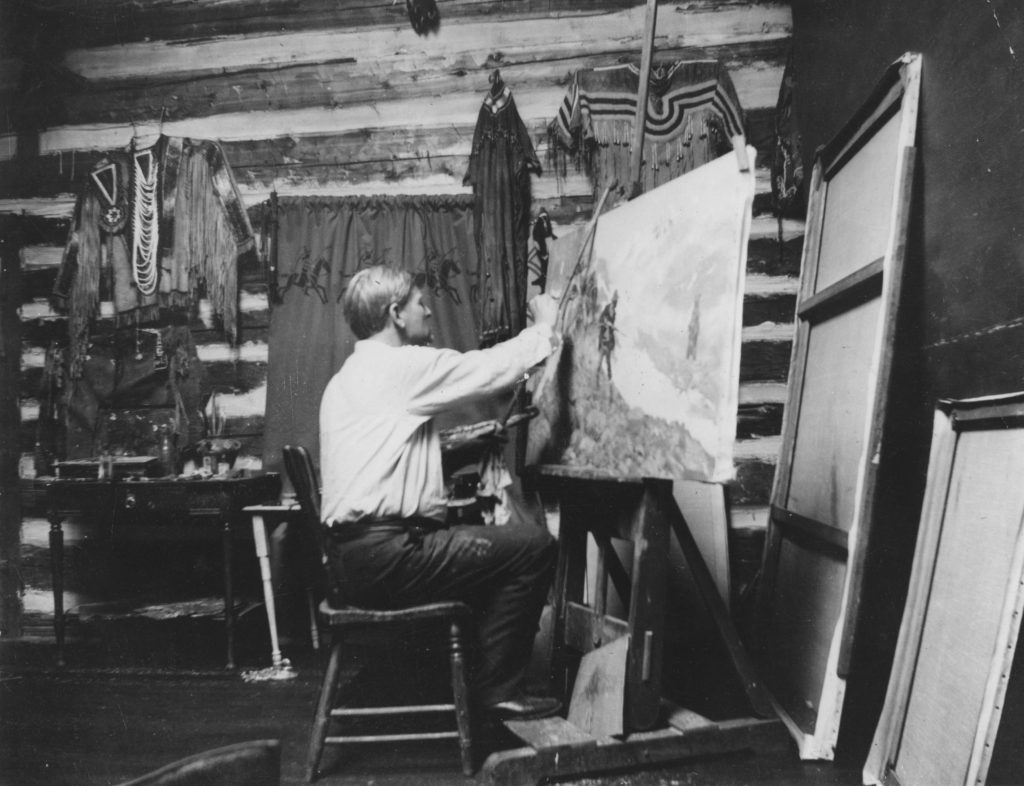

Few folks—other than John Wayne possibly— have done more to shape the Western imagination than Charles M. Russell, who at age 16 hightailed it from Missouri to Montana to be a cowboy. “Russell’s fascination with the West started as a young boy from reading dime novels and hearing stories of his uncles, William and Charles Bent, recklessly exploring the untamed western wilderness,” says Sarah Adcock, associate curator of the C.M. Russell Museum in Great Falls, Montana. Realizing that his fascination was not going away, it was his parents who sent Russell to Big Sky country. “Sadly, by the time he arrived,” Adcock continues, “the West was changing and many of the stories he had heard were becoming just that—stories. Within a few years after Russell’s arrival, Native Americans were pushed to reservations and the wide-open cattle ranges were fenced in. Russell’s work captures an idealized and romanticized view of a West that had passed, but through an open and tolerant lens of all cultures.”

The man behind the canvas painted what he knew. Russell was apprenticed to a hunter and trader for two years before hitching up with several cattle outfits, sketching all types of frontier scenes before branching out as a fulltime artist just before the turn of the 20th century. “The settings and people were real, all based on Russell’s acute observations from his days as a cowboy,” Adcock says of the self-taught talent whose experience gave him an authentic leg up. Even if a bit more glossy than gritty, his depictions of the Old American West created an indelible impression that endures to this day.

Russell’s portraits of American Indians and the American cowboy are among his most popular works. “For Russell, the American cowboys was a hardworking, practical man that embodies the values of perseverance, dedication, and respect for his fellow man,” Adcock says of a perspective that John Wayne, having owned his own ranch in real life, shared. In turn, Russell was no stranger to Hollywood. “Russell surrounded himself with Hollywood greats like William S. Hart and Will Rogers,” Adcock says. “They were not just friends but took inspiration from Charlie’s work and incorporated it into their Hollywood roles—choosing more realistic and rugged costumes that were true instead of the gaudy getups some movie stars would wear in Westerns. Even his protégé, Joe De Yong, would go on to be a Hollywood costume designer and art consultant for many Western films.” Charlie and the Duke had a friend in common, too—director John Ford. Like Wayne in his chosen medium, Russell was nothing if not prolific, working in oil, watercolor, sculpture and even writing, producing a whopping 4,000-plus works—a remarkable visual record of the West. Some of the works most important to his legacy are housed at the C.M. Russell Museum, a Western art complex that includes the artist’s home and studio, both National Historic Landmarks. But it’s also possible to see his influence straight from the comfort of your living room. With streaming, Rio Bravo is always on somewhere.