The life of decorated combat veteran and novelist Karl Marlantes is—like the man himself—one for the books.

Written by Jenn Thornton

Few writers have a more fascinating story to tell than Karl Marlantes. The Washington State-based author of three books—two novels, Matterhorn and Deep River, and the memoir What It Is Like To Go to War—went from small-town Oregon to the halls of Yale, was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University, then served as a Marine in Vietnam, earning the Navy Cross, the Bronze Star, two Navy Commendation Medals for valor, two Purple Hearts and 10 air medals. Marlantes also appeared in Ken Burns’ extraordinary documentary series The Vietnam War, providing some of its most poignant moments.

Marlantes is like America itself—complicated, more than one thing. Of Greek and Finnish descent, he is a product of both cultures; one open, the other resolute. He nearly flunked 1st grade because he couldn’t read, yet went on to become a great writer. He played football but had a stunning intellect that made him something of an outlier in a community of loggers and fisherman. He joined the Marines but loved literature. He wrote his first book in his twenties, but did not see it published until his fifties.

Currently finishing a new novel, Marlantes talks about the chapters of his remarkable life.

Karl—your story is so unbelievable, only a novelist could dream it up. Tell me about it.

I was born on the 24th of December, Christmas Eve, in Astoria, Oregon. My town, Seaside, didn’t have a hospital. My father was fighting in the Battle of the Bulge when I was born and he didn’t know I was on the planet until February. So that’s kind of an interesting start to life. There’s wonderful stories about growing up in a logging town and sort of being—I don’t know what to call it—I guess smart. There were really important people in my life. My father went to college on the GI Bill and became a high school teacher. The GI Bill was amazingly important because he was from a poor background. My mother grew up in a logging camp and totally poor— I mean, no-shoes poor. The librarian gave me books to read, so did the Lutheran minister.

Our backyard, so to speak, wasn’t very large. I think less than a dozen kids in my class went to college. At that time you could work in the woods for over $13 an hour, which is the equivalent of $60 or $70 an hour today. Unions were very strong. So my friends wondered why I would spend all that time and money to go to college. They’d say, “You could be making $12 and with your brains you’ll be a superintendent no time.” That was sort of the big picture.

How did you end up at Yale?

When I took the National Merit Scholarship test it asked where I wanted to go to college if I won. I put down Yale, Harvard and Stanford. Well, I won the scholarship and was accepted to all three without even applying. I just got telegrams from them inviting me to come. I tell that to people today and they don’t believe it.

Because it sounds made up! Talk about a totally different world.

Oh yeah. I enrolled as a physics major and the required entry course was called Mathematical Concepts of Physics, which assumed calculus. We didn’t have calculus at Seaside High School. Yale grades from zero to one-hundred. I dropped out with a four. So, I get into a calculus class. I’m trying to pay attention and just not doing really well. The teacher, a grad student, says to me, “Marlantes, you do really badly on the tests, but when you’re talking in class, it seems like you really understand things and have a lot of interesting things to say about calculus.” Then, he says, “Have you ever tried working?” I honestly didn’t understand—I thought, when you’re done with class, you’re done, right? In Seaside, I only went to class. I didn’t think you had to do other stuff. No one told me that. Needless to say, I ended up as a Ranking Scholar but it took me a bit of time.

When did you join the Marines?

When I was a teenager. I joined the Marines through PLC—Platoon Leaders Class. Basically it’s boot camp. I was a lance corporal in the Marine Corps Reserve and got my commission when I graduated in ’67.

What made you want to serve?

It wasn’t just one thing. There was a draft, which was sort of like income taxes. I don’t know anybody that likes to pay their income tax, but they do it because it keeps the Republic going and we have to repair the roads and everything. The boys I grew up with sort of saw the draft the same way. You do your bit because everybody owes the country at some time. That was the first thing. The second was that most everybody’s father and uncle were WWII veterans. My father was a WWII veteran, and when you see the medals over the fireplace, and the bullet that they took out of my uncle’s leg, it’s like, well, OK. The other thing was that the guys from the football team tended to join the Marine Corps. They’d go down to someplace called San Diego and come back with something we never saw called a suntan. I swear they were 4 inches wider in the shoulders, and they walked up and down Broadway like they owned the place. I was 16 or 17, and I remember thinking, I don’t know what all that is, but dammit, I want some of that.

A completely different education. Tell me about being a Marine.

The Marine Corps is an initiatory experience. There’s only one way you can do what they train you to do and that’s to be brave. You have to go through an experience where you change from being a child to valuing the group. I grew up real fast in the Marine Corps. In Vietnam, I was responsible for other people. I had to be. It’s not just because I was a lieutenant; I mean, the squad leaders in my company were 19-year-old kids. They had 12 people reporting to them, and they made life and death decisions for those people.

This leads me to Matterhorn. It was very well received but published decades after you were in Vietnam. Why so long?

I actually wrote it in the ‘70s. It was 1,700 pages and just really awful. So I started to read books about character development and plot structure. Things like that helped. I kept working on it, and it got better and better, and then I tried to get it published. I got like 100 rejection letters. People would say, we lost the war, nobody’s interested, we could never sell this. Finally, around 2008, I just thought, well, maybe my grandchildren will read the typescript.

When Matterhorn finally was published you became a kind of literary sensation. Then you released your memoir What It Is Like To Go To War, which really resonates with veterans.

I feel enormously proud of its impact on veterans. It is taught at the Naval War College, the Air Force Academy, the Naval Academy and West Point, and the feedback from those who’ve been in combat is very meaningful to me.

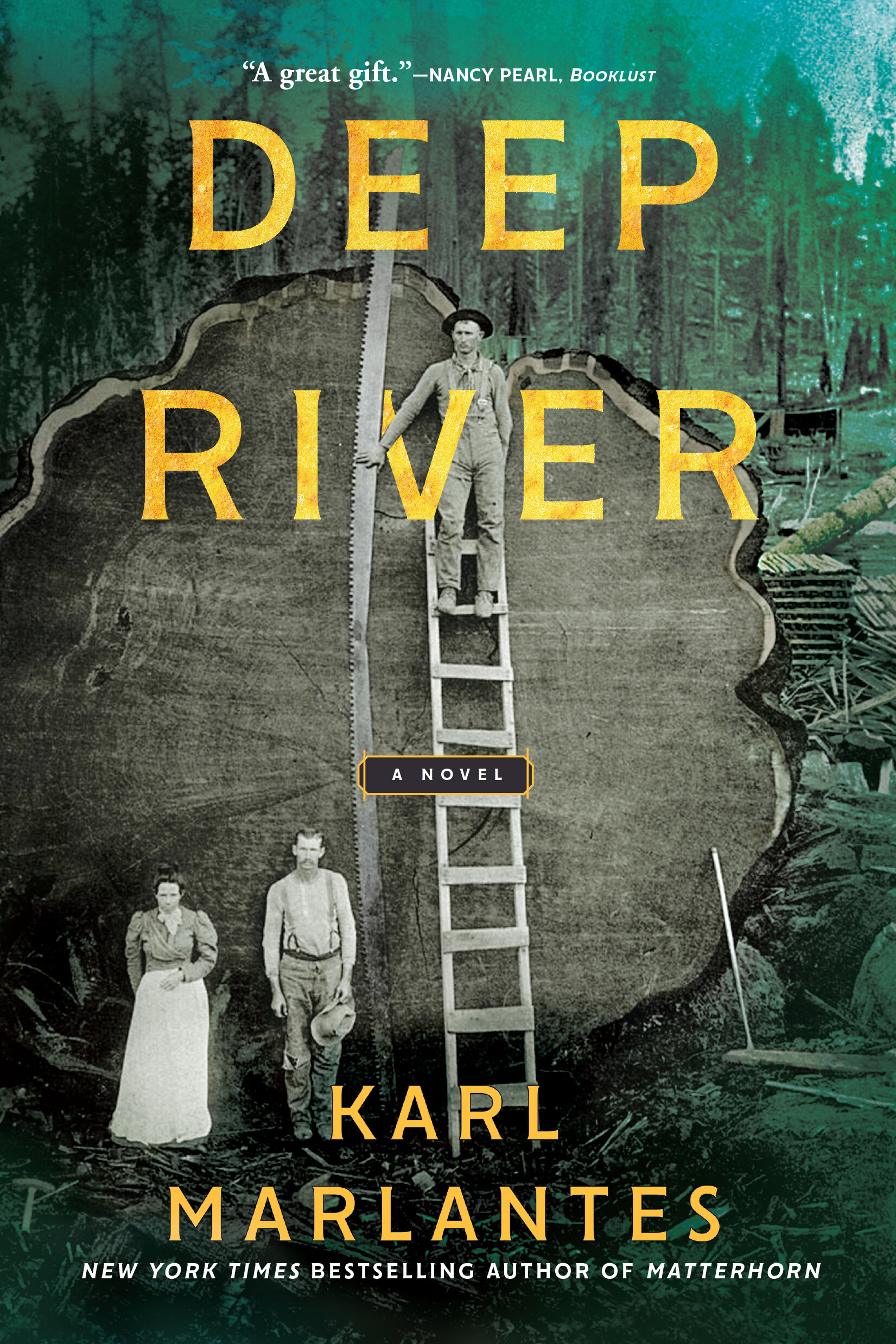

Let’s pivot to Deep River, which wraps in a lot of subjects, all familiar to you—logging, the labor movement, love. It’s very visceral. You can smell the timber, hear it cracking. It also describes the Finnish experience in America, which you don’t really hear about. Is that because the Finns are generally more stoic in nature?

A culture that basically goes only four or five months a year without snow and ice is going to produce pretty stern people. So the resoluteness that I describe in the novel is a real thing in Finnish culture called sisu. There is a sense of toughness and stubbornness. When I was a kid, if I fell down and scraped my knee, my mother would just say, “Stand up. Where’s your sisu?” It’s what beat the Russians in the Winter War. Every other country in Europe fell to the Red Army except Finland.

That kind of strength was necessary in the logging industry—it was dangerous work.

Yes, and brutally hard. I think five of my friends lost their fathers, all loggers. I still remember how the floor would tremble as the logging trucks went by. Details like that are really important for a book.

How much of Deep River came from stories you heard growing up?

Oh, most of it. The fishing scenes are from my own experience; my grandfather was a commercial fisherman. I began working with him in 8th grade when he lost a leg on a log boom. The logging scenes came from when we would go out to the woods as little boys. It was exciting, we just loved it. We’d go out on our bicycles and they’d chase us away. So we’d hide the bikes and sneak into the woods and they’d chase us away. My friends became loggers, my relatives.

Do you think being around that toughness helped you in the Marines?

Oh absolutely. Where I grew up, people died when they went to work. That’s unusual today but it was a common experience when I was a kid.

Who are the writers that really speak to you?

Tolstoy is my hero. Dostoevsky. Those two are very important to me. JD Salinger’s short stories are great, and he’s also a veteran. Norman Mailer was important for Matterhorn. I’m a big Michener guy. When I hear myself saying these names, they’re all older writers, not the newer ones. Quite frankly, now that I’m writing myself, I don’t have much time.

And you’re on deadline to finish your next novel.

Yes, tentatively titled The Winner. Hopefully it will be out by Christmas.