For cultural preservationist and one-time park ranger Doug Leen, chasing down remnants of America’s past for future generations is both passion and pursuit.

Written by Jenn Thornton

Doug Leen is, by nature and admission, “a sucker for preservation,” which not only explains his current restoration of an 1899 tugboat, but the 1899 house in Seattle he renovated before that. And don’t even get him started on old cars and tractors, he warns. At 74, residing in a one-room log house on a roadless island and “loving every minute,” Doug is now in the business of preserving history by creating vivid reproductions of original WPA national park prints created during the New Deal era through his venture Ranger Doug’s Enterprises.

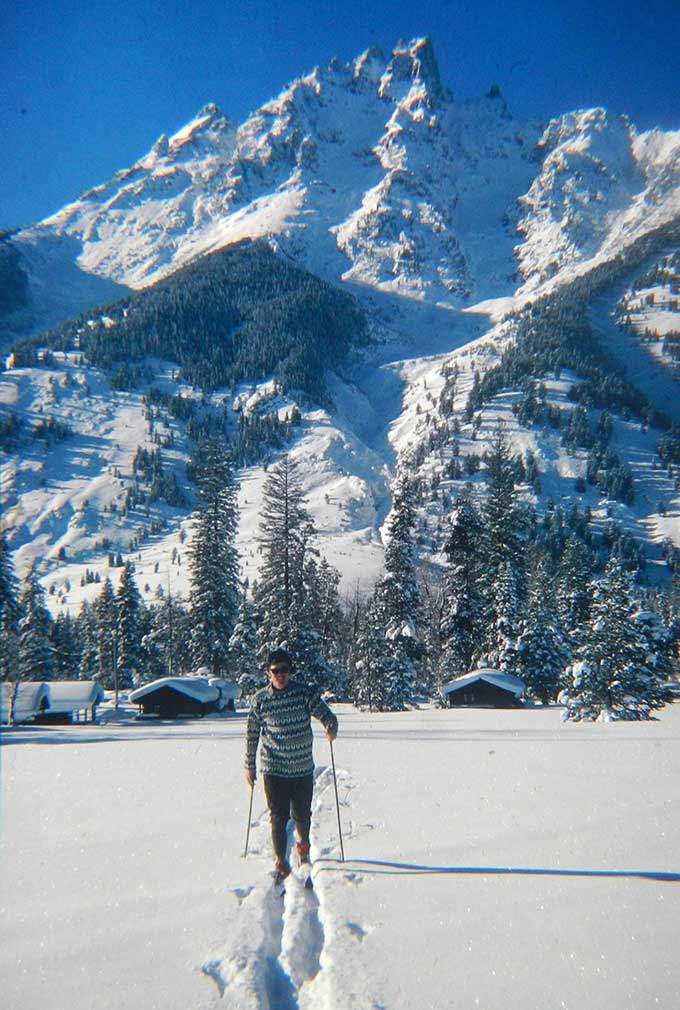

A native of Washington State, Leen has deep ties to the land. He hails from a camping family and has been doing it all his life in some form or fashion, be it a Boy Scout to a Navy Seabee who “camped for two years” on the beach in Vietnam and, while there, penned a letter to John Wayne suggesting that perhaps the star of “The Fighting Seabees” might consider becoming an honorary member. Or a longtime park ranger at Grand Teton National Park. Doug went on to become a city dentist in Seattle, then a rural one in Alaska, where, back in the great outdoors, he administered to the dental health of native villages in the bush and along the Arctic coast. He even practiced at a hospital in Antarctica. So much for hanging it up. “Who wants to retire?” he asks.

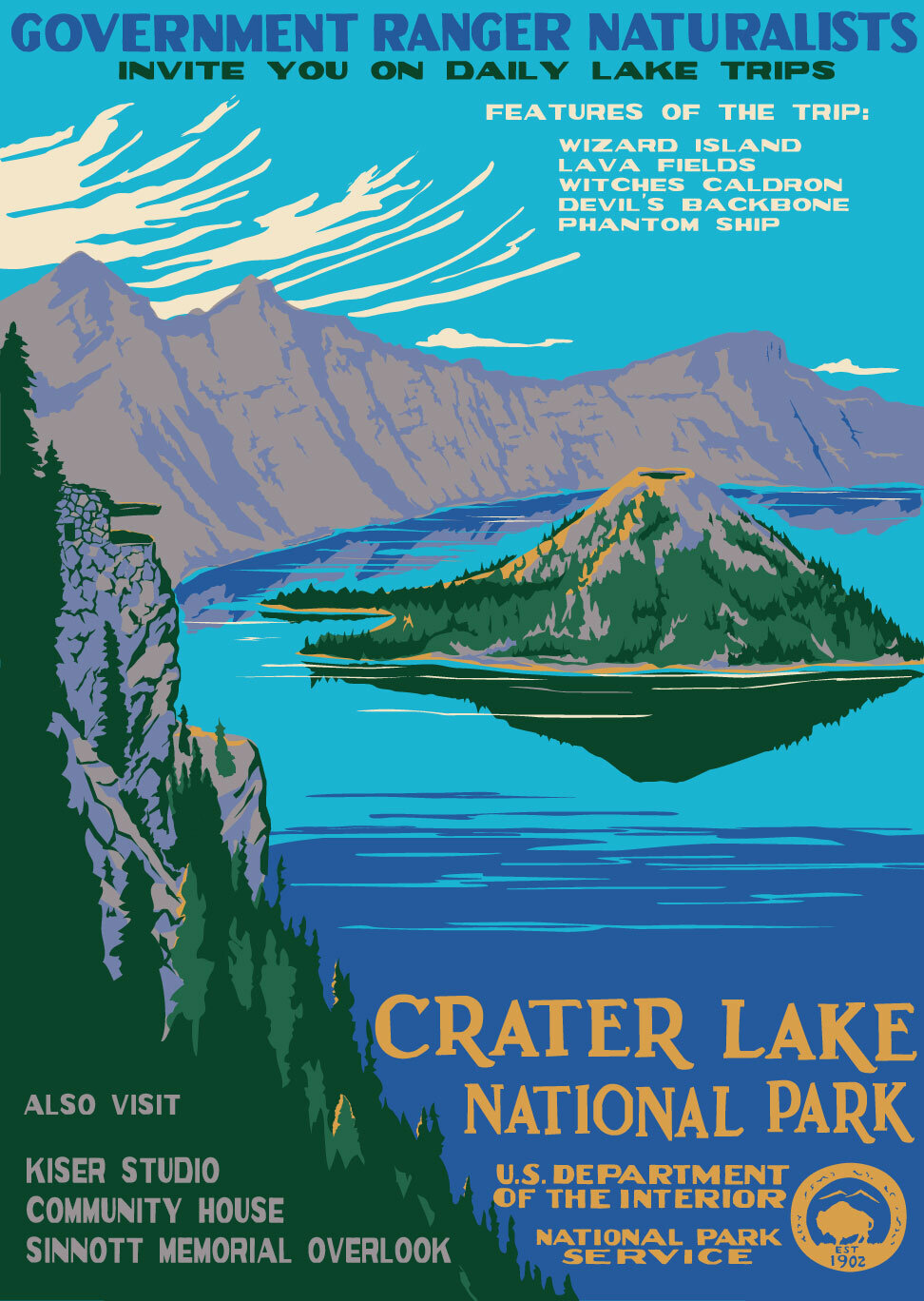

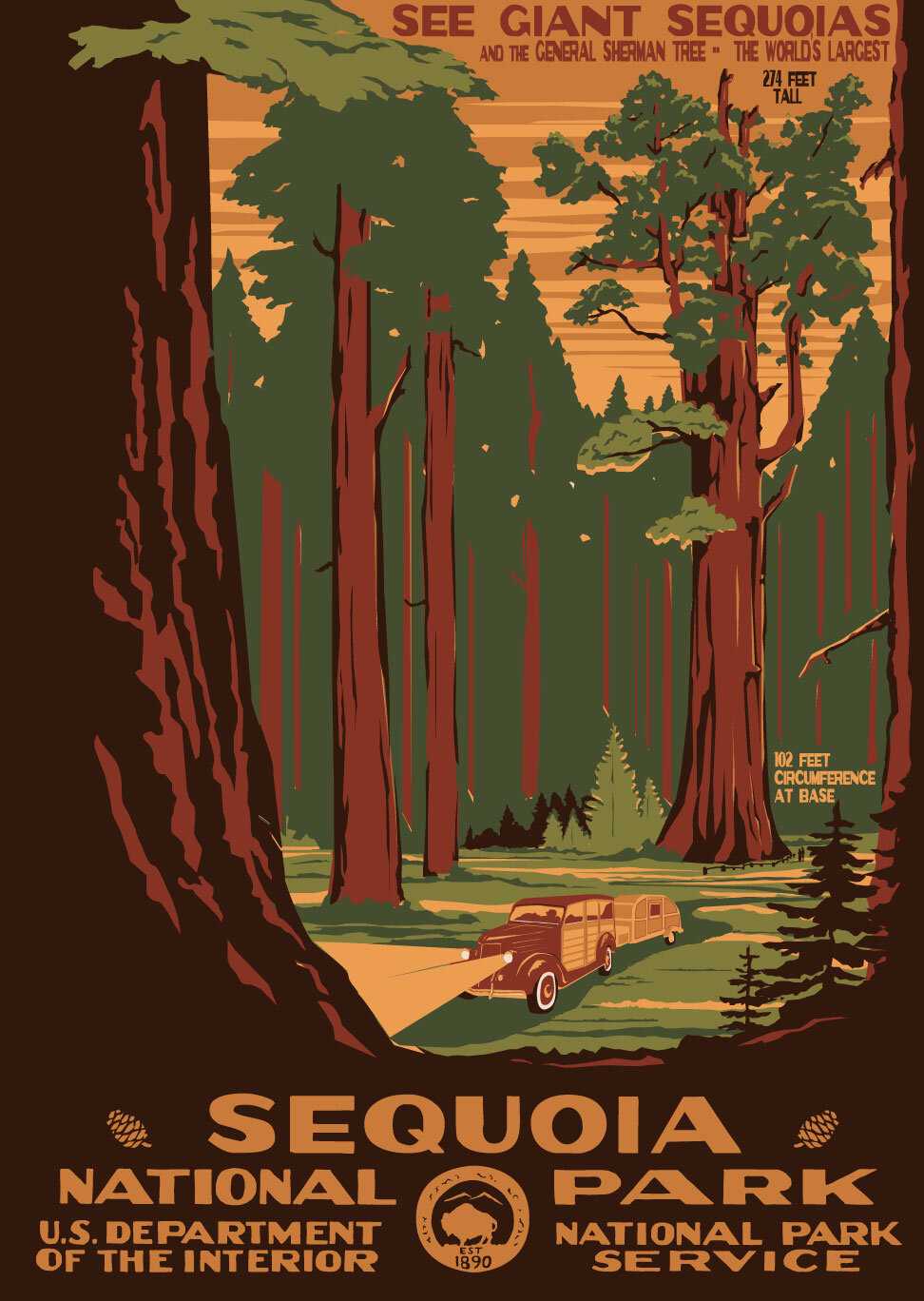

Clearly not the man with the alias “Ranger of the Lost Art” who’s on a quest to track down all the WPA’s original national park posters—an extremely small number. Complicating matters: “The WPA were prolific producers but lousy record keepers, which makes this picture fuzzy,” says Doug, whose knack for making uncanny discoveries first showed itself in 1971, when he saved a WPA Grand Teton poster headed for a burn-pile, then, in 1994, finding a Grand Canyon National Park print. He also found a host of black and white negatives squirrelled away in a file drawer at the National Park Archives at Harpers Ferry, WV. He restored the posters and the discoveries snowballed—originals turned up in garages and attics. Doug’s search—a patchwork approach of working from tips, sifting through junk stores and crisscrossing the country that he describes as “half Sherlock Holmes and half Forrest Gump”—has yielded an impressive haul. “When I would find a print, I would attempt to buy it and eventually had control over 10 prints,” he says. Doug donated this cache to the NPS Archives (two went on to the Department of the Interior Museum).

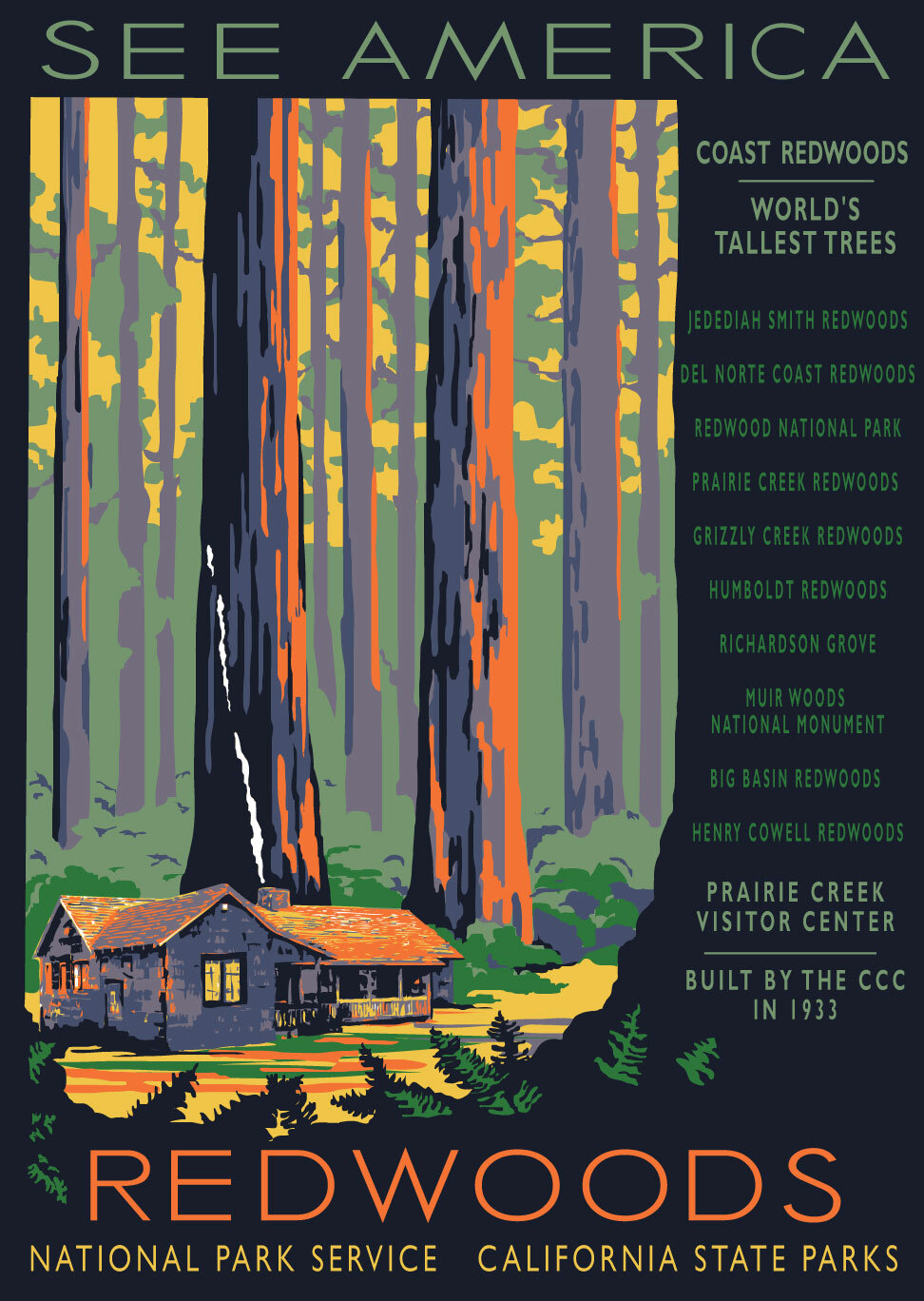

Now through Ranger Doug’s Enterprises, he creates and publishes fresh designs in the WPA style. “We’re not selling just a poster, we’re selling the history of the park,” notes Doug, who is only half-joking when he says his mission is to “hang a WPA poster in every home in America.” As of this writing he’s sold just under 240,000 posters toward that aim, generating almost $10 million for the NPS in the process. For him, the reason is obvious: This land was made for you and me. “Who doesn’t like the huge log entrance at Mt. Rainier, or the Prairie Creek Visitor’s Center in Redwoods, or the beautiful stone-crafted bridges and tunnels in Great Smoky National Park? America is unique among nations in that we created a National Park Service—lands set aside for all to enjoy. It’s that simple.”

“We’re not selling just a poster, we’re selling the history of the park. ”

— Doug Leen

Photos: (c) Ranger Doug’s Enterprises. Graphics: With Permission of Ranger Doug’s Enterprises