John Wayne rounding up horses for a scene in Sons of Katie Elder (1965). Image by John R. Hamilton, courtesy of John Wayne Enterprises

John Wayne Enterprises and the John R. Hamilton Archives were proud to collaborate with photography veteran Laurie Kratochvil to bring the new photography Exhibition “Hollywood and the American West” to the public, currently on exhibition at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum from February 3 – May 14, 2017. This week John Wayne Enterprises sat down with curator Laurie Kratochvil to learn all her secrets in curating an exhibition.

What is your background in photography?

My first experience with photography was in the 9th grade. I worked at Newport Beach, CA based “Road and Track” magazine as my after school job. I had the chance to observe how photographers worked with editors and how editors assigned stories. I fell in love with the personality of photography.

How has the appreciation of photography evolved since you started?

It has evolved incredibly just in the last 40 years. When I first started photography, it was not really accepted as a fine art. Now, photography has become something you collect. There are art galleries and shows devoted to photography as well as million dollar sales for single prints. Recently, as in the last 5 years, people have become very interested in not only vintage prints but also the provenance of the print, whether it comes from a famous person, directly from the artist, or if it was in the archive of a well known magazine like Life or Look. Photography has become mainstream in some ways and high end in other ways. Everyone is able to access it now. The digital revolution has a lot to do with that.

How did you become involved in this exhibition?

John Wayne Enterprises contacted me several years ago. They had recently acquired the analog archive of photographer John R. Hamilton and were interested in having somebody help pull it all together. I live in New York and they are located in California so I started traveling back and forth every couple of months, spending a week or two at a time going through the collection. My strategy was to pull the top 100 pictures I thought the public would want to see and get them in good condition. This photography had been sitting in John Hamilton’s files for years and many of the negatives had become scratched or had dirt on them. We did quite a bit of work to bring these 100 pictures back to their original condition. After cleaning and scanning them, we were interested in getting the work in the public eye. We participated in important shows such as Art Basel in Miami and a big show in Hollywood during Oscar week.

John Wayne, Howard Hawks, Charlene Holt and James Caan traveling between takes while filming El Dorado (1966). Image by John R. Hamilton, courtesy of John Wayne Enterprises

What was the inspiration for putting this exhibition together?

When we first started working with the archive we were amazed at the breadth of John Hamilton’s work. He would go on movie sets and shoot the action scenes, or if he couldn’t shoot an action scene, he would capture scenery. The next day he might be shooting the stuntmen, or a stagecoach chase. As John worked on the movie sets he also became friends with some of the stars. John would get permission from his friends to photograph them at home. This variety of shots meant that John’s archives represent an incredible record of the American West through a Hollywood viewpoint. In going through the archives, Amy Shepherd at John Wayne Enterprises and the John Hamilton Collection and I realized the negatives showed “movie moments” vs. real situations and unique behind the scenes perspectives of the actors. These moments, combined with beautiful landscapes and portraits all came together to create a great show that we felt captured the making of an American Western.

Describe your process for curating an exhibition?

When I first start looking at photographs I always feel a little overwhelmed. I start eliminating pictures that don’t peak my interest, selecting ones that do and laying them out on either a corkboard or a table. Then I begin sequencing them, leaving it up somewhere where I can observe it through out the day. Every time I walk by I may notice something new, or try a new combination. It is really a process of elimination.

One of the things I learned through working at magazines was a story needs to have a beginning, a middle, and an end. The same thing needs to happen with an exhibit.

When you are curating an exhibition, what are you looking to show?

I am looking to show the uniqueness or style of the photographer and the mystery or the uniqueness of the photography. In other words, what makes a photographer good, in my opinion, is what he sees and what he is able to capture in that moment. And when you have a good photographer, you have a consistency to capturing that moment. Now, you could say that the moment exists and the photographer simply captures it. Or you could say that the photographer creates the moment. I think John did both but he had a way of capturing a moment that made people feel very comfortable. I want to try and pick the moment from his photographs that is the most personal, the most intimate, that says the most between two people. I am looking for emotion, for mystery, for intrigue.

A behind-the-scenes shot from Legend of the Long Ranger (1981). Image by John R. Hamilton, courtesy of John Wayne Enterprises

Do you find it challenging to curate an exhibit when the photographer is no longer living? What special steps do you take to honor the photographer and his vision?

I think it is important to do your homework on the photographer. Fortunately, there is a lot of material on John Hamilton in the archive. When he wasn’t shooting he was putting together stories that he could submit to magazines or putting together books that he wanted to publish. Additionally, he also recorded what was going on at a shoot, how he got a picture, or what the circumstances of the shoot were. Being able to read his notes was very helpful in understanding how Hamilton felt about his work, and what he was hoping to show through his photographs.

It was also helpful that John was a strong editor of his own work. He printed many of what he considered his best pictures many different ways. That being said, over the years people’s interest change and we have also been able to find some real gems within his work that maybe he didn’t see the first time around.

Did curating hollywood and the american west present any unique challenges?

I often had to remind myself when looking at an image that what it was capturing was not “real” but instead, a movie scene! That was a unique thing about this exhibit. Also, I think mixing landscape and more traditional art photography with Hollywood portraits was a challenge. In the end, I was happy with how it all blended together because I think it all spoke to John as a photographer.

What would you like the public to take away from Hamilton’s work?

For one thing, the unique period that John worked in. This was the golden age of cowboy movies. When they had a stagecoach going across the land and horses running behind it, that wasn’t digitally produced. It was real. It is wonderful that work has been documented both in film and through John’s photography. I think that is his legacy.

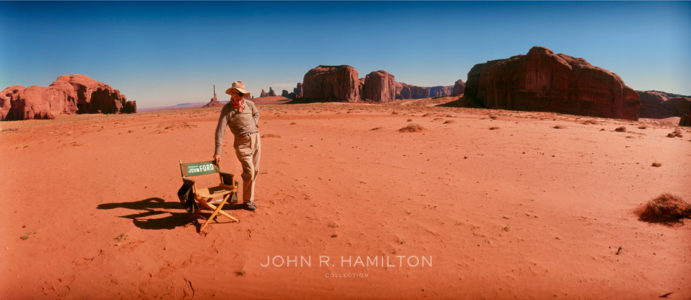

Director John Ford in Monument Valley on the set of Cheyenne Autumn (1964). Image by John R. Hamilton, courtesy of John Wayne Enterprises

Are there any specific pieces in the exhibit that you want to highlight, or that you find personally moving?

One of my absolute favorites was taken in what I believe is Monument Valley. It is just these lonely Hollywood fans sitting out in the middle of the American West. And, of course, the incredible panorama of John Ford in Monument Valley is an iconographic picture that everybody knows and is absolutely spectacular. I think the other one of my all time favorites is Kirk Douglas, standing in his “front yard”, which is his trailer that has been built by some of the crew, with a white picket fence and a little umbrella with a table. Finally, I really love the landscapes. The picture of the covered wagons going across the fields is incredible. It doesn’t get more American than that.

Why do you think Hamilton’s photos continue to resonate today, decades after his career?

They are real and timeless moments. A lot of these pictures could have been taken yesterday. There is a black and white picture of John Wayne in the car that looks just like a family snapshot. It is not easy to get pictures that can resonate, have that much energy, are candid and also are a good photograph. I think John was able to capture that.

Talk about john r. Hamilton’s legacy and the impact of his work.

John’s work lives on because it continues to resonate with people from all industries, including other photographers. Love of celebrity, love of the American West, and love of the American Dream has never changed. His themes, the types of things he was photographing, they connect with people just as they connected with people 50 years ago. A good photograph lasts and that is the true sign of a fantastic artist.

Laurie Kratochvil holding a Kirk Douglas image by John R. Hamilton. Photo courtesy of John Wayne Enterprises.

Laurie Kratochvil is a photography dealer and appraiser, as well as a consultant on visual projects that include magazines, books, the internet and film. She began her career at the Los Angeles Times as a photography editor and went on to work for numerous national publications before joining Rolling Stone Magazine in 1982. During her twelve years there as photo editor, Kratochvil saw the magazine win every major photography award including the National Magazine Award.While working for Rolling Stone, Kratochvil edited a number of books, including the New York Times best seller, Rolling Stone: The Photographs. She has curated several photography exhibitions in the United States and Europe: she has been a frequent panelist and lecturer, and has judged numerous photography competitions.

Kratochvil was the founding photography editor for In Style Magazine and worked there until 2005 before leaving to start her own visual consulting business, working with consumer magazines such as Self, O the Oprah Magazine, Bloomberg Personal, Men’s Health and Essence. In 2009 she was hired by Reader’s Digest Development to consult on new titles as well as the magazine’s international editions.

Kratochvil’s book projects include Africa by Herb Ritts, CUBA-Picturing Change by E. Wright Ledbetter, Mil Besos by Ruven Afanador, and Cyclops by Albert Watson, as well as Watson’s two-volume book on Las Vegas that was published in the fall of 2010. In 2011 she edited Pearls, Tears of the Sea. She recently completed work on another book with Ruven Afanador.

Kratochvil is a board member of The Society of Publication Design, a jury member of World Press, and a faculty member in the continuing education program at The International Center for Photography. A native of Newport Beach, CA, Kratochvil lives in New York City and Southold, New York.