The Journal takes a deep dive on John Wayne’s friend and frequent director John Ford.

Written by Jenn Thornton

Before there was Martin Scorsese and Robert DeNiro, there was John Wayne and John Ford. The duo’s on- and off-screen relationship spanned 50 years and 14 films. To mark the 50th anniversary of the death of Duke’s legendary mentor, friend, and director, The Journal looks back at Ford, the man, and some of the myth, too.

A son of Irish immigrants, John Ford was born in Cape Elizabeth, Maine, a handful of years before the turn of the 20th century. He was not, however, born “John Ford.” Just as he would eventually give his discovery, a young propman named Marion Morrison, the strapping alias John Wayne, the director took “Ford” as his surname, but he would retain his legal name throughout his life—Sean O’Feeney. His father was another Sean, as was Wayne’s character in The Quiet Man (1952).

Before he was the great director, Ford paid his dues in the trenches of early Hollywood. Turns out, he was a damn good eye back then, too. Not only could he spot a landscape, he could spot talent when he saw it. One day that was the man who would anoint John Wayne. As the actor proclaimed in his unfinished autobiography, he met Ford on set. After inquiring about Duke’s football career, Ford challenged the young man in a friendly way. In preparing for a skirmish, Ford got the better of him and Duke went down. The upstart actor did not, however, back down. Instead, Duke schemed to trip up Ford, literally, only to accidentally knock the director in the chest. As Wayne told it, and as the story goes in the John Wayne: The Genuine Article, “Suddenly, ‘Ford was splattered in his own plaster mud on his own backside.’” The rest is cinematic history.

What history! Ford rose becoming the winningest film director in history, with a haul that includes a whopping four Best Director Oscars for The Informer (1935), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), How Green Was My Valley (1941) and The Quiet Man, starring John Wayne and his leading lady and dear friend, Maureen O’Hara. The director only showed at one of the ceremonies at which the golden trophies were awarded, though, proclaiming once to be drunk, once to be fishing, and once because he was at war. That war was WWII and Ford was heading documentary filmmaking for the United States Navy. His footage of the Japanese attack on Midway Island—during which he was wounded in an aerial attack—became the documentary The Battle of Midway. In yet another coup for Ford, the film went on to score an Oscar for best short subject at the Academy Awards in 1942. As part of his service, Ford also filmed the invasion of Normandy and, after the war, led a team that gathered photographic evidence for the Nuremberg trials. He later retired from the United States Naval Reserve at the rank of Rear Admiral.

Given Duke’s close ties to Ford, it is not a coincidence that some of actor’s most indelible performances in WWII movies were as Navy men, including Naval flier turned Hollywood screenwriter Frank “Spig” Wead in The Wings of Eagles (1957) and Lt. J.G. “Rusty” Ryan in They Were Expendable (1945)—both directed by Ford, naturally, with the latter picture co-written by Wead himself.

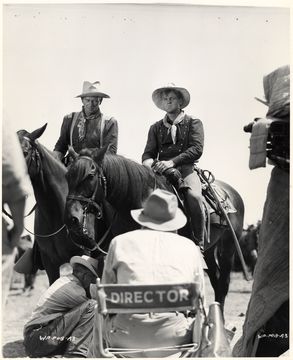

Of Duke and Ford’s many films together, however, arguably none are more iconic than their Westerns Stagecoach (1939) and The Searchers (1956), the latter picture prompting Wayne to write Ford in a letter starting with “Dear Pappy” and continuing with “Back to ‘The Searchers’ – it’s just a wonderful picture. You got great performances out of everyone, and it has a raw brutalness without any pettiness or meanness. All I can say is – thanks again, Coach.” Legions of fans and critics then and now agree. Both The Searchers and Stagecoach are among AFI’s top 10 Westerns of all time, ranked no. 1 and no. 9, respectively. It seemed that no matter their success apart, Ford and Wayne were drawn back together and to the Western landscapes they loved. Concluding a letter to Duke dated Nov. 2, 1957, written while the actor was overseas filming John Huston’s The Barbarian and the Geisha (1958), Ford wrote: “P.S. Would you like to do Western sometime?” The answer to that question would come the following year in the form of the duo’s next film, The Horse Soldiers (1959).

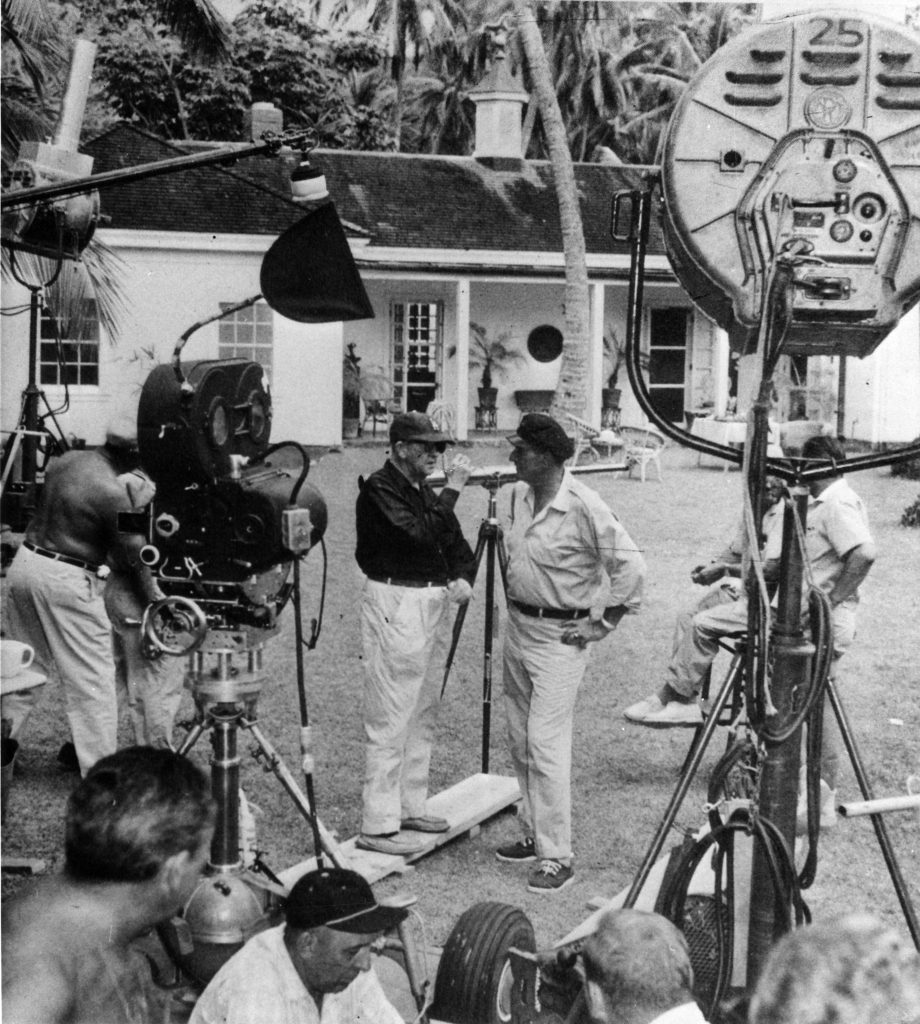

It wasn’t all shoot ‘em ups, though. In 1963, Wayne and Ford reunited for the adventure comedy Donovan’s Reef, their last film together—but not their last tie. Ironically, after an on-set accident that took place 25 years prior, Hollywood’s visionary directors lost sight in one of his eyes. Not unlike Wayne’s iconic character Rooster Cogburn in True Grit (1969), Ford gritted it out too, wearing an eyepatch for the rest of his days. Pappy and the Duke—together again.