LEADING LADIES, FROM HOLLYWOOD’S GOLDEN AGE TO TODAY, PRESENT A VITAL FEMALE PORTRAIT OF THE GRIT AND GLORY OF THE AMERICAN WEST

Written by Constance Dunn

“It’ is that quality possessed by some which draws all others with its magnetic force,” wrote Elinor Glyn in the title card of the same-named 1927 silent movie. The movie’s breakout star was, of course, Clara Bow, the original “It Girl” who had this rare characteristic—an unmistakable combination of visual allure and an innate, unique flourish that could be reliably conveyed on screen—in spades. Whether by careful design on the part of the performer, or the luck of nature, the “It” factor, if it is to translate, must always be projected as a thing of organic spontaneity, so that no matter what else is happening on screen, the audience can’t help but keep their eyes fixed on the actor possessing it.

In honor of Women’s History Month, we call attention to leading ladies, past and present, who’ve lit up the screens of Hollywood’s most notable Westerns. Women’s History Month has been commemorated in the U.S. since 1987, when Congress first designated it in March, and Ronald Reagan became the first president to issue a proclamation in its observance, calling “upon all Americans to mark this month with appropriate observances to honor the achievements of American women.” Among those achievements has been the visual projection of strength—often salted with a fierce sense of individualism and femininity—that marks the onscreen portrayals of the women of the American West.

Many of Tinseltown’s most lauded works in this genre have also starred John Wayne, whose to-the-point pillar of strength provided an ideal companion to steel magnolias like Maureen O’Hara, playing his estranged love interest in the Westerns Rio Grande (1950), McLintock! (1963) and Big Jake (1971). By contrast is the vulnerability of raven-haired Gail Russell, who appeared in three Wayne films, (to O’Hara’s five), including the role of a kindly frontier Quaker who tenderly nurses The Duke, as an injured outlaw besotted with her, back to health in Angel and the Badman (1947), which was also the first film that Wayne produced.

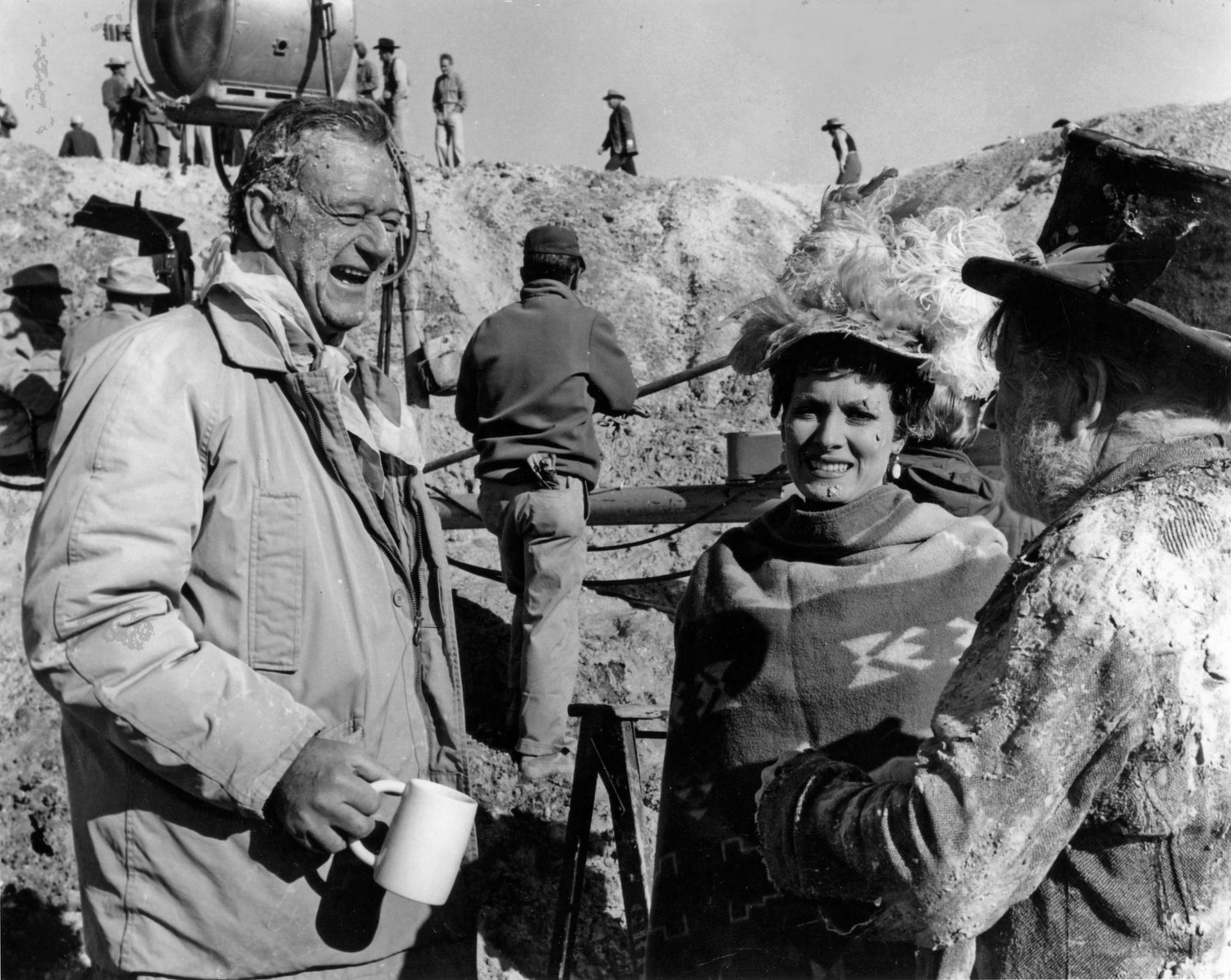

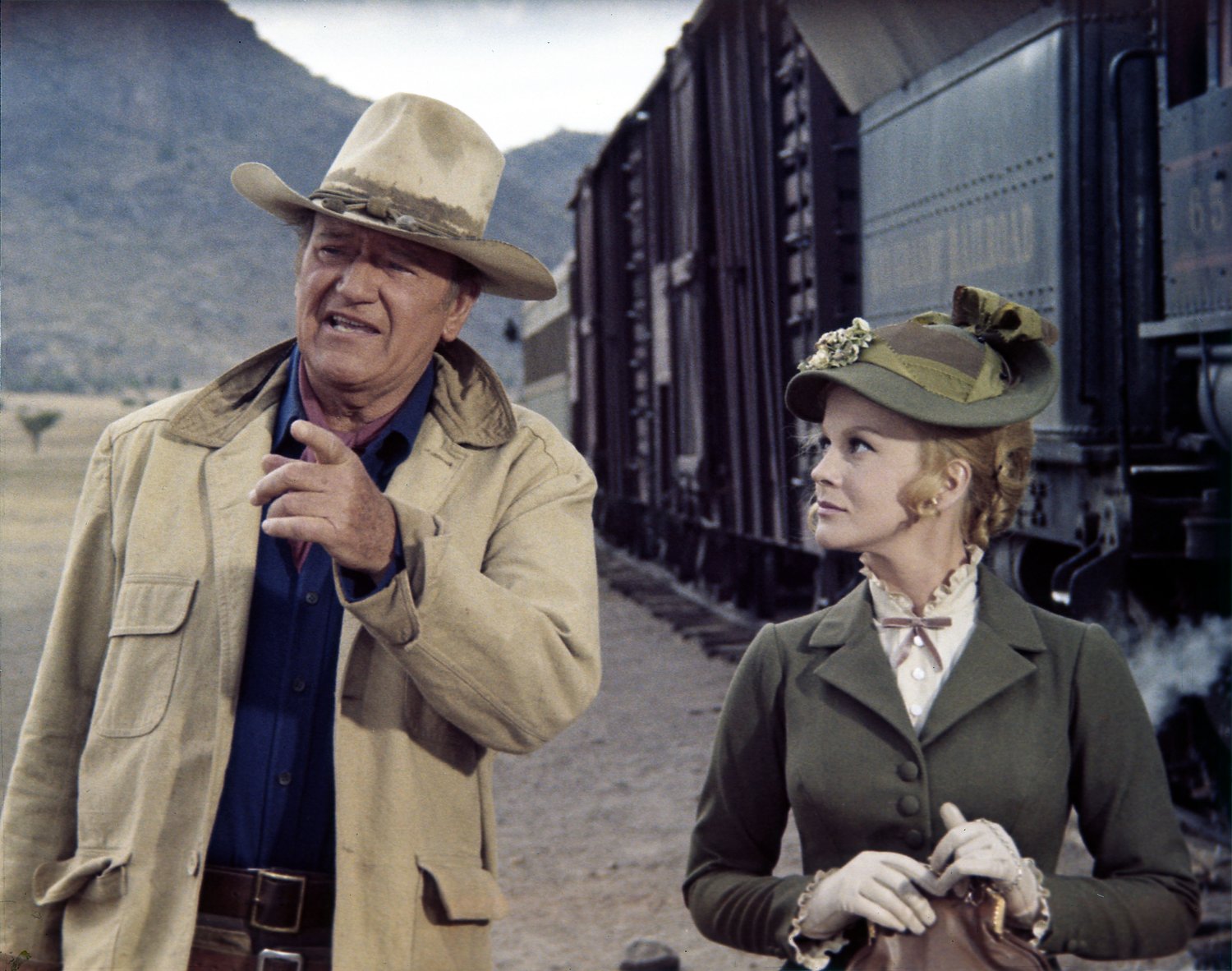

Even Westerns where the leading lady was not a Wayne love interest per se, showcased women of the American West as possessing heroic levels of loyalty and resolve. It’s hard to imagine a conventional female lead in the place of plucky frontier beauty Joanne Dru, who doesn’t utter a peep, much less howl, when an arrow pierces her shoulder during battle in 1948’s Red River. Or actress Ann-Margret as a train robber’s widow in The Train Robbers (1973), teaming up with a trio of Civil War veterans, John Wayne’s character Lane among them, to recover a lost cache of gold and clear her husband’s name. (The ending reveals a twist for her character; however, she gets high marks for pluck, particularly in battle.) In addition to being a leading man, Wayne was also a successful producer whose well-honed eye for talent had him casting “It”-factor stars like Lauren Bacall, who appeared in two Wayne films, Blood Alley (1955), and later, as a single mother to a young boy and an unwavering ally to Wayne’s vulnerable, dying gunslinger in his final film, The Shootist (1976).

Only a couple of decades later, Sharon Stone would turn traditional Western casting on its head by playing a believably tough, bent-on-revenge gunfighter in acclaimed The Quick and the Dead (1995). Likewise for Regina King, who recently portrayed braid-wearing outlaw leader Trudy Smith in The Harder They Fall (2021), a high-styled take on the New Western featuring a cast of all-black actors.

No matter the year of their film’s release, what leading ladies of the genre all share is “It,” along with the ability to project a particular female strength rarely seen onscreen outside the Western, where it’s a staple. Perhaps it’s no coincidence, then, that 1927—the same year that Clara Bow projected “that quality possessed by some which draws all others with its magnetic force” to filmgoers around the globe—was also the year that young Marion Morrison landed his first job in pictures, as a prop man and day laborer at Fox Studios, thereby starting the countdown to just a few years later when he’d similarly enthrall audiences by appearing onscreen in all of his John Wayne glory.