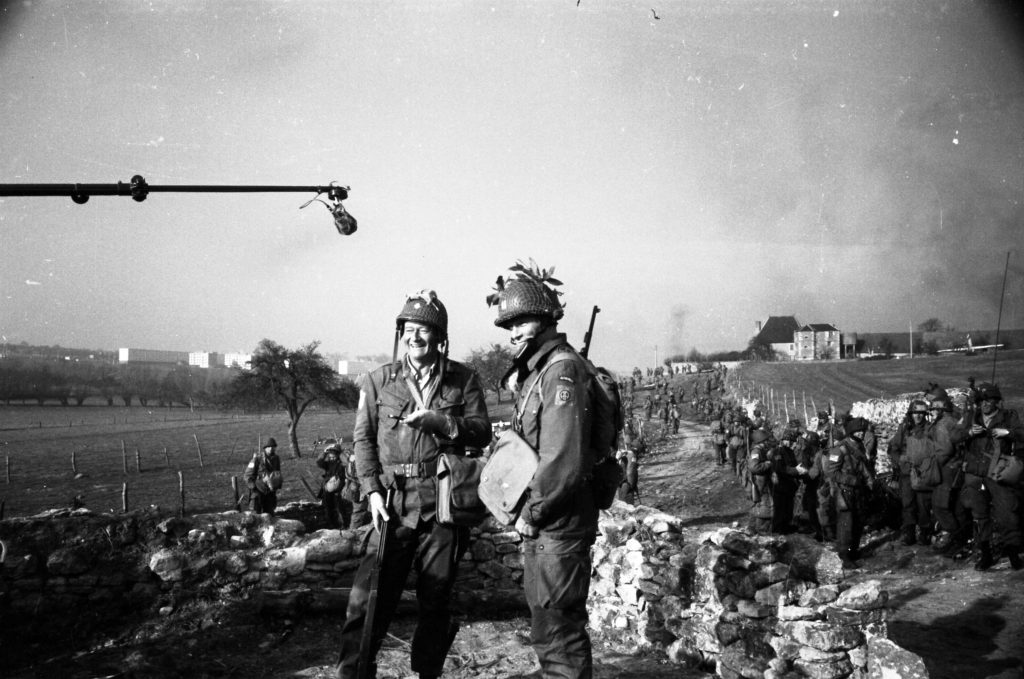

On the eve of the 80th anniversary of D-Day, a look back at The Longest Day.

Written by Jenn Thornton

Few people have uncommon courage, which is why that rarest of things continues to inspire years, decades and even centuries after those who have exercised it are gone. Their deeds may have been lofty and idealistic, or quiet and diligently achieved. Some courageous names are well known to us, far more are not. Others should be.

Those who have seen The Longest Day (1962)—20th Century Fox’s epic accounting of D-Day featuring John Wayne and a sweeping international cast of American, British, French and German actors—know all about the uncommon courage of the man Wayne portrayed in the film, Lt. Col. Benjamin Hayes Vandervoort, and undoubtedly admire his heroics on June 6, 1944, when the then 27-year-old parachuted into Nazi-held France as part of the Allied invasion of Europe. Code-named Overlord, the historically seminal action was deemed the “Great Crusade” in General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Order of the Day, which was addressed to the 132,000 “Soldiers, Sailors, and Airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force.”

If the scale of the invasion was Herculean, it was heroic because those who went into battle did so knowing that causalities would be heavy, if not certain. And still, they made the jumps. Stormed the beaches. Took the guns. Liberated the towns.

Among their number was one Lt. Col. Vandervoort—and there was only one. Like the men he fought alongside, he had a job and he did it. How he did it, however, was tailor-made for a Hollywood telling. This was a man, after all, who broke his ankle on the jump into Normandy with the Army’s 82nd Airborne Division. But rather than retreat, Lt. Col. Vandervoort refused to be evacuated. He ordered a medic to stitch his boot as tight as it needed to be to fight on. Receiving little more than first-aid for his excruciating injury, he organized and personally led the troops from his battalion through enemy territory to defend the town Sainte-Mere-Eglise. Sacrificing his personal safety and subjecting himself to fire from every side, Lt. Col. Vandervoort and his men withstood repeated counterattacks from the enemy.

History would never forget that day and, 40 years later, neither had Ret. Army Col. Benjamin Vandervoort. In an article published in the Beaufort Gazette, Vandervoort recounted his ordeal with laser-like recall: Soaring over the Channel toward the French coast, he looked out of the 82 Airborne’s lead plane for the designated drop zone and saw “ships of every description” below him and plane after plane behind him. Prior to training for the mission for more than half a year, “we had been fighting in Italy and Sicily and we were seasoned veterans,” said Vandervoort of combat experience that would prove pivotal. Dropped over Sainte-Mère-Église, “Eight or 10 men were shot in the air,” Vandervoort told the paper. “One landed on a church steeple and hung there a couple of hours watching the action until a German found him and cut him down.” As for Vandervoort himself, “I landed in a cow pasture and immediately broke my leg. I deliberately slid toward a dark area so I would not be visible and get shot, and there in the bushes was a sunken place that caught my ankle.” His march to victory continued.

After D-Day, Lt. Col. Vandervoort jumped into Holland as part of Operation Market Garden and he was severely injured during the Battle of the Bulge. As the Beaufort Gazette reported, “He spent 18 months in hospitals recovering from the loss of an eye and other head wounds.” They would end his military career. But Vandervoort would go on to serve his country in other ways, working for the Foreign Service, the Dept. of the Army and the Central Intelligence Agency.

How, then, does a man like Vandervoort—twice awarded the Distinguished Service Cross as well as a Bronze Star, three Purple Hearts, the French Croix de Guerre and Holland’s Bronze Lion—start milling about the crowd like a regular Joe? Presumably just by doing it. In the Beaufort Gazette, Vandervoort’s Hilton Head Island friends remembered him as “plain, friendly, unassuming Ben.” One might think Vandervoort would have seen enough beaches for a lifetime, but in Hilton Head, South Carolina, the WWII hero experienced something approximating normal life. He traveled—“Col. And Mrs. Benjamin H. Vandervoort returned home after a two-moth Mediterranean cruise aboard a Norwegian freighter,” The Island Packet reported—and, in August of 1977, the same paper conveyed that Benjamin H. Vandervoort of Marsh Wren Road had once again been called for duty, this time as a juror. What’s more, the Beaufort Gazette documented the daily, drama-free happenings of his retirement, noting that Vandervoort enjoyed “golf, gardening and fishing.” Regular guy, extraordinary life, uncommon courage. On Nov. 18, 1990, Vandervoort died at age 73. He could never have outlived his wartime exploits, immortalized with box-office swagger by John Wayne in The Longest Day. We should remember them, too, and all the acts of bravery and sacrifice that were never immortalized but nevertheless serve as examples of the uncommon courage that helped liberate the world from tyranny. They were many. But when the Army decided to honor one officer from each of the nation’s wars for outstanding combat service, The Island Packet reported: “It chose Col. Vandervoort from World War II.”