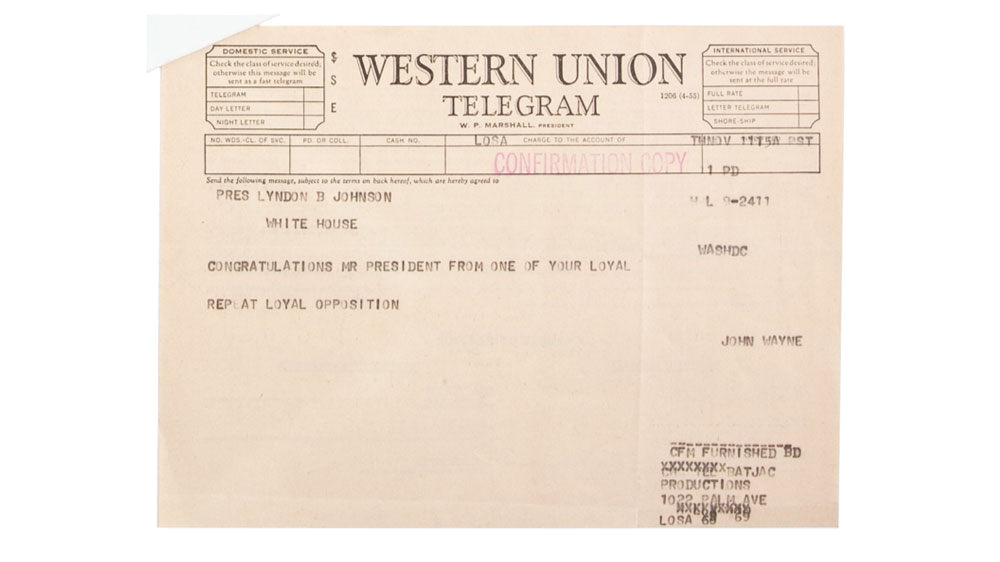

From the John Wayne Archive, a congratulatory telegram Wayne sent to President Lyndon B. Johnson after winning the 1963 presidential election. Photo courtesy of John Wayne Enterprises

Written by Michael Goldman

In early 2012, when John Wayne Enterprises asked me to begin researching John Wayne: The Genuine Article, a New York Times Bestselling book published in 2013, I had the privilege of going into John Wayne’s personal Archive and examining his private papers first-hand. The book was conceptualized to be a “personal” look at Duke in his own words and point of view on various topics of deep importance to him. And few subjects were more important to John Wayne than the welfare of the country that gave him the opportunity to become a movie star and one of the most famous people who ever lived. He was, in other words, a deeply political creature.

More specifically, Duke was, as most people know, a rock-ribbed Conservative who, from the time he first campaigned for Dwight D. Eisenhower in the 1950s, routinely befriended, supported, raised money for, campaigned for, and voted for Republican candidates and causes. This was not news when I found his letters concerning the political causes he was passionate about. What was enlightening, however, was the fact that his Archive contained irrefutable proof that John Wayne considered himself an American first, Republican second, and was committed to the principles of civility and respect even when standing up for his ideals.

Indeed, I learned that a huge number of his closest friends were Hollywood Liberals: Kirk Douglas, Gregory Peck, Paul Newman, just to name a few. Duke would debate them in his letters, as he did Newman on December 13, 1961, when they exchanged views as to whether the Kennedy Administration was “Socialistic” or doing enough to defend the Middle Class. The debates were never personal—they were always respectful, intimate and caring even. When I thought about it, Duke’s mentor and lifelong best friend was famed director John Ford, known to sometimes have very liberal leanings, and yet, two men in Hollywood could not have been closer.

I was blown away to find in Duke’s datebook that in the 1970’s, John Wayne regularly had lunches with famed cinematographer Haskell Wexler, who wrote Duke a thank-you note in December of 1977 for “the horse poetry gift” John Wayne had given him, promising that “you have love from all of us who worked with you.” I knew Wexler was a legendary Hollywood Liberal in that era, and until he died last year, and that they ferociously disagreed about the Vietnam War. So in 2012, as I documented, I called Wexler and demanded an explanation for his friendship with John Wayne. Why were they wining, dining, and exchanging poetry?

Wexler explained that he was the director of the series of Great Western Bank commercials that Duke starred in in the 1970’s, and the two realized they had far more in common than not during that association—the Old West, horses, poetry, filmmaking, and much more. He insisted John Wayne was consumed with the notion of “fairness and humaneness” in all things, political and otherwise, and that the notion of Duke refusing to consider “the other side” of issues or to have respect for those who disagreed with his strongly held views was merely “a caricature.”

I also learned how John Wayne sent President Nixon many letters of support as Watergate broke. Then, as letters and speeches suggest, he appeared to become disappointed in Nixon when he realized not only were the charges against Nixon true, but that perhaps even worse, he had taken Nixon’s word for it when he said they were not true. To John Wayne, a man’s word was his bond. And so, some later letters and speeches, including a notable speech in 1974 that we quote in the book, indicate an increasing plea for civility, truthfulness, and mutual understanding that, he argued, was more important than mere politics.

Thus, if you haven’t already read John Wayne: The Genuine Article, don’t be surprised to learn that President Jimmy Carter penned the foreword—a politician who, as Carter articulates, John Wayne never voted for, and whom he largely disagreed with on a whole host of issues. We detail how and why Duke broke with his Republican brethren to lobby Senators of both parties to ratify Carter’s drive to approve the Panama Canal Treaties, solely because he felt they were good for the country. As he supported Carter on that issue, his close friend, Ronald Reagan, who was preparing to run against Carter, was angered, and a back/forth letter exchange broke out between them, as we document. What is instructive is, what ended their disagreement had nothing to do with one man giving in or changing his position. It had to do with two friends eventually comprehending that their dispute might be harmful to their relationship. And so, they simply knocked it off.

As John Wayne eventually became sick, the Archives indicate that Carter visited him and called to check up on him when he was hospitalized, and of course, he signed the bill granting Duke posthumously a Congressional Gold Medal and eulogized him to the country as “the genuine article,” which is where the book’s sub-title comes from. And it was Carter who stated in in his foreword that what we need today is “more John Waynes.”

Being just a couple weeks from a hugely divisive, bitter national election, Duke’s example of courtesy and country first is not a bad one to emulate. After all, his relationship with Carter began exactly the same way that he welcomed the other Democratic presidents who were elected during his years in the national spotlight into office—Kennedy and LBJ. All three of them received a telegram from him upon winning. That telegram was identical in all three cases, and read simply, “Congratulations sir, from one of the loyal opposition.”

Michael Goldman wrote the 2013 award-winning book that examined letters and documents from John Wayne’s personal archive—John Wayne: The Genuine Article. Goldman has authored six books about major media-related topics, legends, and institutions, including co-authoring a textbook on filmmaking, an acclaimed coffee-table book on director Clint Eastwood’s filmmaking techniques called Clint Eastwood: Master Filmmaker at Work, an authoritative history of the USC School of Cinematic Arts, and more. He has also written for acclaimed film journals like American Cinematographer, CineMontage, Millimeter, Post magazine, Variety, and consumer publications like the LA Times, Orange County Register, Philadelphia Inquirer and others. Goldman podcasts interviews with filmmakers monthly at the Studio Daily site in a series called Podcasts from the Front Lines. You can learn more about his work at his Website—www.hollywood-scribe.com.