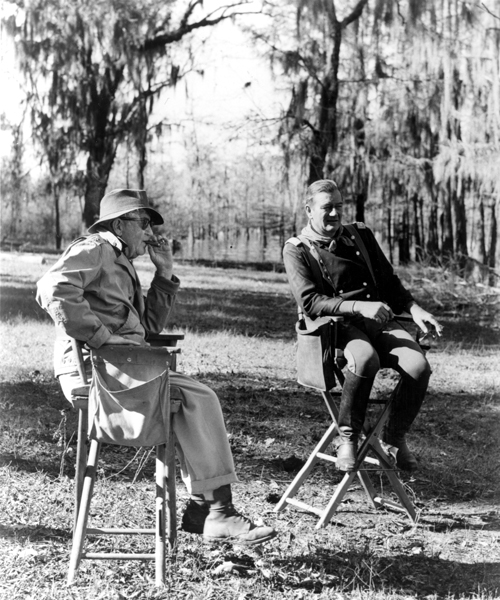

Seated from left- Ward Bond, John Wayne, and John Ford behind-the-scenes of The Wings of Eagles (1957), photo courtesy of MGM

Written by Michael Goldman

The personal relationship between John Wayne and legendary film director John Ford has been analyzed and debated over the years. It’s well known Ford was Duke’s mentor, having met him when Duke was still a college student earning money doing prop and stunt work at Fox Studios as the Great Depression dawned. He eventually decided to put Duke in front of his cameras as an extra in 1928; gave him his first speaking role in a film called Salute in 1929; and recommended him to fellow director Raoul Walsh as a leading man in The Big Trail. When that movie flopped, though, John Wayne was, for years, relegated to starring in B-level serial Westerns, possibly for the rest of his career had Ford not made him the leading man in 1939’s Stagecoach, the film that rocketed Duke into stardom. Over decades, the two of them worked on over 20 motion pictures together, including Duke’s early appearances as an extra, cementing one of the most prolific director/actor collaborations in the medium’s history.

None of which explains why exactly the two of them became best friends. The famously cantankerous Ford, after all, rode Duke mercilessly during the making of Stagecoach and other films, not convinced for many years that he was truly a fine actor. They fundamentally disagreed on various political matters, and both had projects, adventures, and headaches of their own that kept them apart for months at a time. And yet, through it all, the pair only grew closer until Ford died on August 31, 1973. The recent 44th anniversary of Ford’s passing gives us good reason to look back at their deep relationship.

John Wayne, Pilar Wayne and John Ford traveling from New York to Southampton aboard the Liberté to see the first James Bond film Dr. No in 1963. Photo courtesy of John Wayne Enterprises

And deep, it was. In fact, Duke made Ford godfather of two of his sons—Patrick and Ethan—and kept a framed and signed 1947 portrait of the man he usually called “Coach” or “Pappy” in his home until the day he died. Indeed, as he wrote in the unfinished biography manuscript of his life located at the John Wayne Archives, Duke described their relationship as “a very fine manly love.” Duke also periodically told Ford directly how he felt, such as in a 1961 letter in which he told Ford that he was “my best friend” and “someone I have a blood kinship with.”

As described in a previous column in this space about their other longtime friend, actor Ward Bond, much of the friendship was built around simple camaraderie—having good times together on set making movies, sailing the world first in Ford’s yacht, “Araner” (on board which Ford reportedly first offered Duke the leading role in Stagecoach), and later, on Duke’s yacht, “The Wild Goose.” This collegial respect and admiration, it appears, began in their relationship’s earliest days. Shortly after they met, Ford tried to prank Duke on set of a film he had hired Duke to crew on. Ford coaxed him into demonstrating his football form, and then intentionally tripped him for a laugh. When Duke responded by, as he wrote in his unfinished biography, asking for “another try” and then knocking over the director so that “Ford was splattered in his own plaster mud on his own backside,” John Wayne’s spunk and determination and failure to be intimidated clearly appealed to Ford.

Indeed, traveling together, drinking, carousing, joking, and more are all documented in dozens of letters in the John Wayne Archive. But the relationship was quite obviously about more than simply having a good time. In fact, from his earliest days on a movie set, it’s clear that John Wayne initially wanted to emulate Ford. Indeed, as he wrote in his biography manuscript, Duke’s initial goal was to become a director himself, and Ford thus became the object of great study by Duke. He wrote that Ford would eventually “teach me everything I know about filmmaking.” Even as Duke rose higher on the movie-star ladder, he never stopped writing Ford for advice, thanking him, confiding to him, offering him help, and apologizing whenever he felt he had offended Ford in some way. Indeed, letters indicate John Wayne wrote Ford at least three times to apologize merely for not returning his call promptly. He wrote in June of 1966 that it was “irresponsible to someone I really love” not to call back. “Please forgive me Coach.”

John Ford and John Wayne on the set of The Horse Soldiers (1959). Photo courtesy of United Artists

The John Wayne Archives are filled with postcards and telegrams back-and-forth between the two men, birthday greetings, and a mutual love for making each other, and their friend Ward Bond, butts of various jokes. But their letters also include Duke pouring out his feelings about his bitter departure from Republic Studios (October 29, 1952), his divorce (June 6, 1953), and much more. Likewise, letters from Ford to John Wayne discuss various casting decisions, deals and failed deals for both projects Duke was and was not involved with, his various social adventures—including in one undated letter, Ford’s annoyance with being stood up by Orson Welles for a scheduled late-night dinner—and much more.

But even the gruff John Ford occasionally let slip directly how personally fond he was of John Wayne, and how much he cared about his welfare. When Duke was in Libya filming Land of the Lost in 1957, for example, Ford wrote him to be careful about toiling under the hot sun.

“Be very careful and wear your hat at all times, and don’t get sunstroke,” Ford wrote Duke on January 25, 1957. “I know, because I spent a winter once on the North African Coast.”

Thus, whenever possible, throughout the years Ford was actively directing, Duke tried to make himself available to Ford if he wanted him. While some have speculated that perhaps Ford took advantage of this loyalty in the sense of pulling Duke away from other beneficial projects, in fact, Ford wrote him on December 7, 1955, to reassure his friend that he would understand if Duke took a competing project. “God knows I want you for the picture, but you mustn’t do it as a sacrifice to yourself,” Ford wrote. “You have been doing that for me for too many years. If you have any chance for a great deal, please be assured that I understand perfectly. After all, nothing ain’t never going to break up our friendship.”

Those who knew Duke well believe the core of the relationship was the innate sense of loyalty that drove both men. Duke always put Ford first, and Ford came to deeply appreciate that. Ford helped Duke launch his career and then become a star, and Duke likewise deeply appreciated that, and felt it was worth the razzing he would periodically get on set from the great director to repay him for Ford’s support from his earliest days in the film industry.

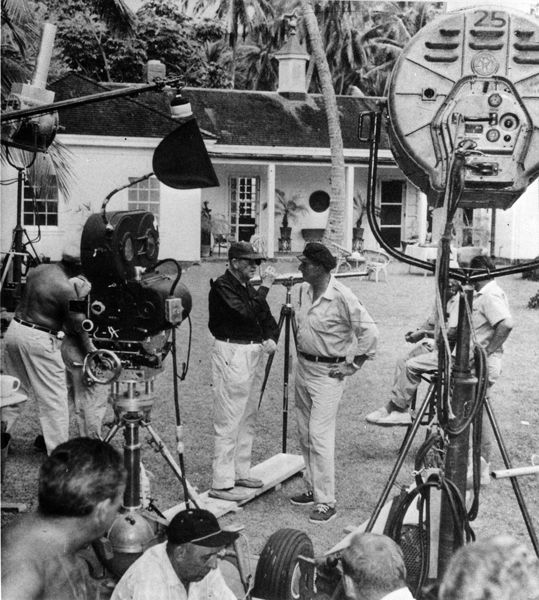

John Ford and John Wayne on the set of Donovan’s Reef (1963). Photo courtesy of Paramount Pictures

“My father had one of the all-time great relationships with John Ford,” Duke’s oldest surviving son, Patrick Wayne, insists. “He had such tremendous respect for [Ford], and credited him with the reasons why he became the success he became. I personally think my dad would have become a success no matter what, but he credited the guy with giving him the break that kicked him off, and he never forgot that.”

Daughter Melinda Wayne Munoz, adds that, in her view, the two men had a father-son relationship. “My opinion was that Uncle Jack was [the one person] who could say anything he wanted to my dad, because he was the one who [believed in him first]. He loved John Ford because Ford gave him his chance. That’s why, if they needed [a stuntman] to jump off a building, my dad would run out there and say ‘I’ll do it.’ I did sometimes think was he mean to my dad [on set]. But I was a little girl looking in, and watching someone direct my father. My father would do it all over again, and never get mad. That’s how much he respected him.”

In any case, one thing is clear—by the time Ford died, they were so close that John Wayne received numerous condolence cards, still located in the John Wayne Archives today, of the variety normally sent to family members. No surprise, then, that John Wayne told a newspaper the day after Ford died that “the man was my heart. There was a communion between us that not many men have. I have never been closer to any person in my life than I have been with Jack.”

Step inside the world of John Wayne and explore priceless memories through our interactive exhibit John Wayne: The Genuine Article. Filled with never-before-seen letters, speeches and handwritten notes, along with hundreds of film props, hats and boots. John Wayne: The Genuine Article ran November 17, 2017 – January 1, 2018 at the Gaylord Opryland Resort & Convention Center in Nashville, Tennessee. If you would like to learn more about the exhibit, including future dates and locations, please subscribe to our email list.

Michael Goldman wrote the 2013 award-winning book that examined letters and documents from John Wayne’s personal archive—John Wayne: The Genuine Article. Goldman has authored six books about major media-related topics, legends, and institutions, including co-authoring a textbook on filmmaking, an acclaimed coffee-table book on director Clint Eastwood’s filmmaking techniques called Clint Eastwood: Master Filmmaker at Work, an authoritative history of the USC School of Cinematic Arts, and more. He has also written for acclaimed film journals like American Cinematographer, CineMontage, DGA Quarterly, Emmy magazine, Millimeter, Post magazine, Variety, and consumer publications like the LA Times, Orange County Register, Philadelphia Inquirer and others. Goldman also podcasts interviews with filmmakers monthly at the Studio Daily site in a series called Podcasts from the Front Lines. You can learn more about his work at his Website—www.hollywood-scribe.com.