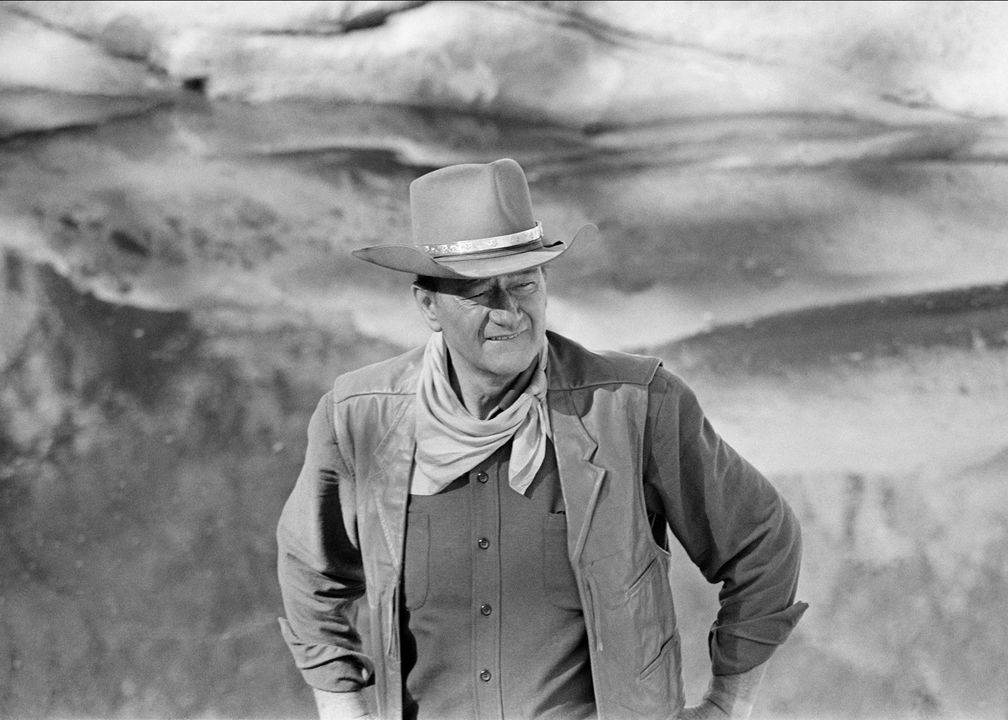

John Wayne on the set of El Dorado (1966). Photo by John R. Hamilton, courtesy of John Wayne Enterprises

Written by Paul Thompson

Americans have always been drawn to frontiers. At its most basic level, it’s a country settled by those willing to cross an ocean and see a world none of their ancestors had laid eyes on, with the hopes of a better life away from Europe; a few hundred years later, the United States sent a crew of men to the moon. We still tell the stories of fur traders, of Lewis and Clark, of the families who blazed the Oregon Trail, and we shape children’s imaginations by showing them rainforest expeditions or deep-sea explorers. But there’s perhaps no greater symbol of the American frontier than the cowboy: smart, self-reliant, brave, rugged. With Westerns, and fascination in the lore of the American West, making a resurgence in pop culture, it’s interesting to look back at the origins of the cowboy in America, and at the roots of our fixation on the West. And no man was more instrumental in shaping our collective image of the cowboy than John Wayne.

Crews Ranch Cowboys, Early 1900s. Photo courtesy of University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History

Almost as soon as the country was settled, the people of the United States began to creep Westward. Around the year 1725, the word “cowboy” made its first appearance in the English language, but it would be years before it took on the meaning we know today. Cowboys led quiet lives bound by routine–tend the cattle, make sure the ranch runs smoothly. Those who came to be called cowboys developed an intricate social and ethical framework, but mostly toiled in anonymity. The job wasn’t yet romanticized, mostly because there was no one around to romanticize it.

The first use of the word “Western” to describe a genre of storytelling came in 1912, in a magazine called Moving Picture World. But it has roots from at least forty years prior. In the early 1870s, Buffalo Bill Cody, who had worked as a bison hunter, scout, and Pony Express delivery boy during his youth in the Kansas territory, started hitting the road, putting on stage performances that depicted cowboys in the American West. These shows were not always driven by narrative; audiences came to gawk at horses, elaborate dress, feats of strength, and so on, though there were reenactments of famous battles from time to time. By the end of the 19th Century, Buffalo Bill had taken his show across America (including a stop at the Chicago World’s Fair) and beyond, touring Europe to the Pope and Queen Victoria.

Original movie poster for Stagecoach (1939). Photo courtesy of Walter Wagner Productions

Throughout Hollywood’s silent film era, which began at the tail end of the 1800s and lasted through 1927, Westerns were among the most popular fare. The Great Train Robbery (1903), which is still taught in colleges today, put the genre on the cutting edge of the new artistic format, using innovative new techniques to tell stories about the West. However, when Hollywood made the move to sound in the late 1920s, it largely left behind the Western, which became relegated to B-movie status, and was not given the same artistic or cultural credence that it received in the decades prior. For the first time, Westerns had to fight for relevancy against glossier stories about towering cities.

Fortunately, the drought wouldn’t last long. In 1939, John Wayne–already a seasoned veteran of B-Western pictures–starred in Stagecoach, which would go on to be one of the most crucial turning points in American cinema. In the picture, Wayne plays a fugitive who escapes prison after learning that his father and brother were murdered. Though he gets briefly entangled in the lives of a band of strangers, his main objective is clear: to find his family’s killer and avenge the deaths. After a string of chases and confrontations, he does just that, before turning himself back over to the law. Of course, he’s allowed to escape. This is an important moment in codifying the cowboy legend in the American psyche. Wayne’s character is a man of principle, and a man of duty; he defies the law only because he’s responding to a higher moral calling. As soon as that destiny is fulfilled, he defers to the rules of the land. (It’s important to remember that Stagecoach extends this code of ethics beyond its hero: when one of Wayne’s enemies prepares for the climactic battle, he’s forced to leave behind his shotgun, as it’s considered a dishonorable weapon. Even in a fight to the death, there are matters of principle.)

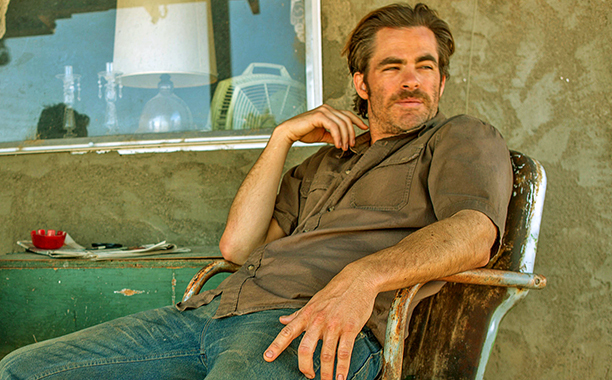

Chris Pine in a scene from the film Hell or High Water (2016). Photo courtesy of Sidney Kimmel Entertainment

As we all know, Wayne went on to be one of the most iconic figures in American popular culture. While not all his pictures in the ensuing decades were Westerns (83 were, however), Wayne as the cowboy was an enduring image, and came to define the term for multiple generations of Americans. He was rugged and hard-nosed, but only as far as his surroundings dictated; he was always fair and virtuous, a man of moral conscience and clear principles. His iconic, Best Actor-winning performance in 1969’s True Grit, argues that these qualities will sustain a man and make him formidable into and beyond middle age.

In recent years, the Western’s popularity has undergone a series of ebbs and flows. As with all forms of storytelling, modern iterations build on what came before. John Wayne’s American cowboy provides a sort of narrative shorthand. Imagine Clint Eastwood’s legendary Westerns without the image of Wayne in our collective unconscious–Dirty Harry and Unforgiven would need to do considerably more cultural exposition, and Eastwood’s actions wouldn’t have the same symbolic weight. A movie like Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained wouldn’t work as such a sharp play on the Western genre and its place in the American psyche.

At the moment, the Western seems to be on an upswing, recapturing the American imagination. Hell or High Water, which updates the Western to grapple with questions about the 2010s economy, was nominated for Best Picture in February; HBO’s Westworld goes so far as to depict a near future where people pay thousands of dollars to simulate the experience of the old West. Every one of these narrative threads can be traced backward through John Wayne, who to this day stands as the most clearly defined cowboy in our cultural heritage.