When it comes to creating and restoring the nose art of historic warbirds, Chad Hill is aces.

Written by Jenn Thornton

“I grew up watching John Wayne movies, and I always loved Flying Tigers,” says Chad Hill, founder of Django Studios. “I never met any of them in real life, but that movie is so cool. It kind of started my love affair and passion for aviation.” Or simply furthered it.

Hill is, like the nose art he creates, and re-creates, for historic aircraft, a throwback. His sensibilities are those of an earlier era. Born in Indiana, just north of Indianapolis, Hill’s father was part of the 366th Tactical Fighter Wing in Vietnam; his uncle was the crew chief of a C-47 in Korea. They took Hill to his first air show when he was six. An admitted “gearhead,” Hill was a born tinkerer and, with everything on his small family farm “from the ‘50s generation,” there was no shortage of things that needed fixing—tractors, tools and other toys, including his father’s 1936 Ford Coupe. Hill commandeered the second floor of his family’s farmhouse and turned it into a creative laboratory for his art, his music and related interests. Hill remembers the farm as “a little time capsule.”

Hill went on to study graphic design and admits that if you asked him then what would he be doing now—including restoring the nose art of America’s warbirds—he “never would have believed it.” Hill’s path, however, suggests otherwise. As a gifted graphic artist, he worked at big-city agencies with clients including Hasbro; for that conglomerate Hill did designs for Trivial Pursuit, Monopoly, Taboo, and Jenga. He then entered sports marketing and did work for NASCAR, specifically Richard Petty and Stewart-Haas Racing, and also for IndyCar, while at the same time getting Django Studios off the ground.

Django Studios brings Hill back around to his love of the retro and rockabilly. (Hill played guitar in a rockabilly band that recorded three albums, one at the famed Sun Studios in Memphis, and he met his wife swing dancing.) Django does all sorts of design work but hits another gear in the aviation and automotive space. It was in a state of rediscovery that returned Hill to his love of aviation. He started surfing warbirds online and after seeing a post on a message board for the Commemorative Air Force, Hill worked up some sketches for their B-24, sent them in for consideration, and was contacted. They said, “‘They’re great. Now do you want to come down and paint it?’ My response was, ‘Oh. Really?’”

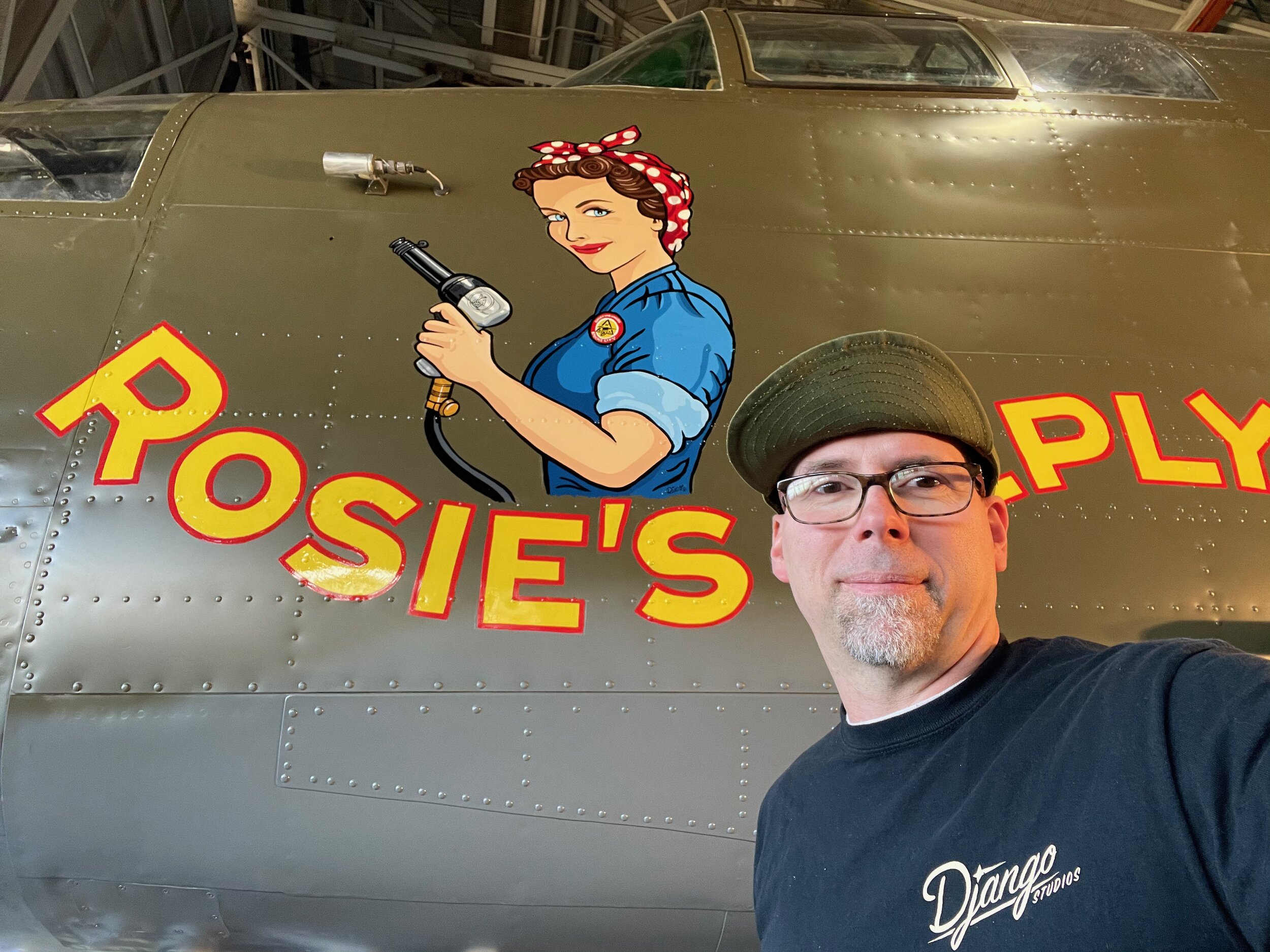

From that wheels-up moment to now, which currently finds Hill prepping for painting projects in England and Pennsylvania, where he’s doing the artwork for a C-53 called Beach City Baby; a WWII P-47 replica cowling in France; and a private commission in Kentucky—Hill has completed four or five planes. This includes That’s All, Brother, a C-47 in San Marcos that was the lead aircraft, Chalk 1 of Serial 7, of the main airborne invasion on the eve of D-Day that dropped 13,000 paratroopers behind enemy lines in Normandy. “That was pretty special,” concedes Hill, who was also tapped for the B-25 Rosie’s Reply, done in honor of the legendary Rosie the Riveter. “I based her on Naomi Parker Frawley, who is the first Rosie.” This work has led Hill to become, as he puts it, “somewhat of an amateur historian, as well.” Now, he says, “I can look at a squadron and start to see which artists worked on which plane, and see the styles emerge. That’s really important in my work.”

Combat pilots are, by nature, competitive. Big missions, big egos. Hill, one the other hand, is strikingly humble. And humbled. He’s met some of the biggest names in flight, including the legendary Jimmy Doolittle’s co-pilot Dick Cole, and the only living triple ace of WWII, Bud Anderson, aged 99, whose likeness Hill is using for the design of a UK-blended gin. His work is at a dozen museums across the country, including the grand-daddy of the aviation world, the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, which acquired Hill’s piece featuring the P-51 Lope’s Hope 3rd.“ To meet these guys, and to do this work, is an unreal experience,” he says. “It’s an honor to be able to read about this history, and to keep that history alive.” An honor, and also an art.

“It’s an honor to be able to read about this history, and to keep that history alive.”

— Chad Hill

Photos courtesy of Chad Hill