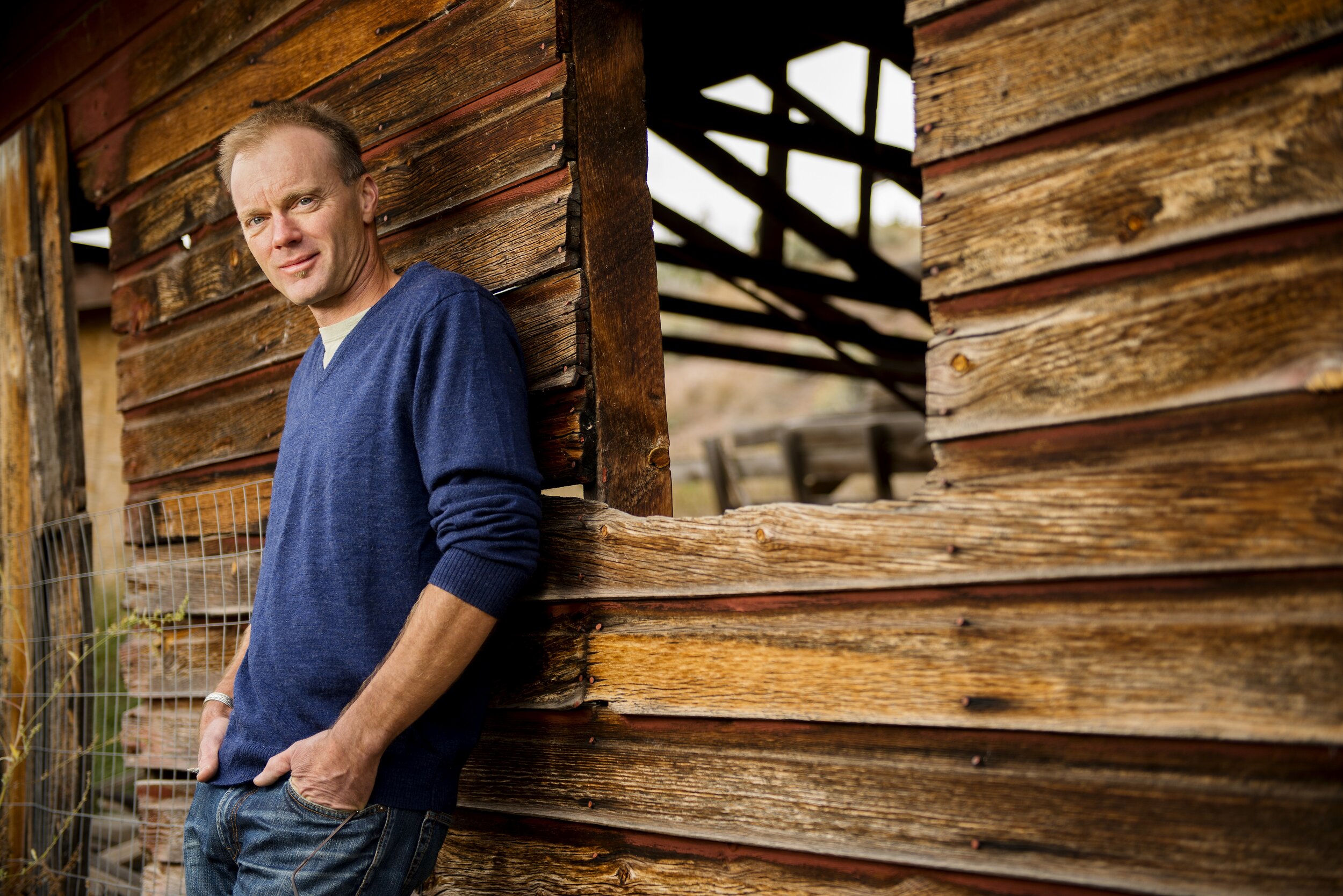

Montana novelist and craftsman Malcolm Brooks builds on his reputation as one of the finest writers of the epic American narrative with Cloudmaker.

Written by Jenn Thornton

Born outside Philadelphia to parents who left Mid-Atlantic life for Southern California, only to find it far too pavemented for their tastes, author Malcolm Brooks came of age in the West. The family eventually made their way to the rural north, settling in the heart of Gold Rush country and hitting its stride. It was there that Brooks—a Field & Stream kind of kid who grew up riding horses and watching Westerns—did what adventurous young men in the country do. He fished, camped, and hunted.

And he read—prolifically, and far above his pay grade. While his peers were knee-deep in juvenile lit like “Where the Red Fern Grows,” the eighth-grade Brooks was wrapping up “Winds of War.” For his teacher, there was only one book to give a boy who wrote about James Michener’s “Centennial” for his book report. The Western epic “Lonesome Dove,” which Brooks credits not only for its great gifts of story and character, but for transforming his life.

Brooks never left the West, nor did he start writing right away. He apprenticed in carpentry and eventually settled in Montana in 1995. He still swings a hammer, and says the real-world balance only makes his fiction richer. It’s hard to imagine it could be better. Like his astonishingly well-received debut “Painted Horses,” the newly released “Cloudmaker” is large in scope, rich in history and tuned to tension. Brooks makes no apologies for the long saga. For a man with an such an uncommon way with words, he’s uses relatively few to make his point: “go big or go home.”

Did growing up in Gold Rush country nurture your love of the West?

Quite a lot actually. I was completely transfixed by it. We used to find mining stuff out in the woods all the time. Pickaxes, shovels, stuff from local tribes. I had a real focus on anything having to do with the American West.

And you read a lot.

All the time. But “Lonesome Dove” really clinched it for me. It was completely transformative and probably the reason that I ultimately became a writer. Once I realized that there was this type of literary effort that could be put into a Western, my whole frame of reference changed.

In terms of craft, and the idea of refining something, do you draw a correlation between carpentry and writing?

Metaphorically you create something like a narrative in the sense that you’ve got to have a foundation, you have to put walls together, put a roof on, and make it all come together into something you can actually live inside of. I think it’s good for writers to do things that are not closely related to the craft of writing and the life of the mind, and to have practical hands-on capabilities, and a different and separate set of skills to inform your vision. I know a lot of people struggle with completing writing projects and they’ve got a million unfinished things lying around. I think the fact that I’ve got this A-to-B-to-C, put-a-period-on-it job, in addition to writing, has partially informed my ability to go the distance with it.

You obviously love an epic. What attracts you that type of storytelling?

I went through a phase where I read relatively short, straightforward coming-of-age novels that had very little in the way of adornment to the prose. Then I got into Jim Harrison and Thomas McGuane who were writing off the wall, nearly satirical novels that at the same time were just perfectly written on a sentence by sentence level. In my early thirties my taste and reading range shifted. I was really blown away by “All the Pretty Horses” by Cormac McCarthy and “The English Patient” by Michael Ondjaatje. It brought me full circle to the big and sweeping. By that point I had young kids. I said if I’m going to stay with this, I need to go big or go home.

True to form, there’s a lot in happening in “Cloudmaker,” starting with the protagonist Houston “Huck” Finn.

I wanted to tell a coming-of-age story as if Mark Twain was writing adventure stories in the golden age of aviation instead of in the Antebellum South.

Huck is an adventurous person. Is this a case of write what you know?

As soon as we got to northern California, my dad turned me loose with a shotgun or rifle to go hunt by myself when I was 14 years old. I love to fish, to camp, backpack and all that. We were always building survival type shelters out in the woods, looking for arrowheads. That’s where the specific American West influence really comes in.

What’s interesting about both your books is that they take place in romanticized times but feel realistic.

This goes back to “Lonesome Dove” as an influence. If you think about it, a pair of Texas Rangers going from Texas to Montana on the surface sounds like a total cliche. But then all these amazing characterizations start to come off the page. You’ve got Augustus McCrae wandering around delivering sort of quasi philosophical pronouncements and whatnot. Reading it, I understood how it was possible to come up with a narrative that just turns the characters loose to do whatever they’re saying and doing. Let them behave like real people on the page, then give them a stage to walk around on and some kind of a crisis in the background. That’s probably a part of why the books come off the way they do. So while they are happening during an archetypal or mythical time in American history, it’s still balanced by realistic characters.

Speaking of mythical, which John Wayne films speak to you?

Well, “The Searchers” and before that, “Red River.” I think John Ford had probably studied what Duke was capable of doing. Darker sorts of roles. “The Searchers” is where that just totally gels. It is so striking on so many levels. I never get tired of the dialogue. Such an epic performance in an epic film. Actually, my youngest son is named Ethan, after Duke’s character in “The Searchers,” and my other son is named Cole for John Grady Cole in “All the Pretty Horses.”

That’s perfect—that says it all.

Absolutely.

Photographs courtesy of Grove Atlantic