When it came to stunts, young John Wayne learned from the best, becoming an accomplished stuntman who devised a few industry standards still seen on screens today.

Written by Constance Dunn

For John Wayne the 1920s and 1930s were an extended master class in all aspects of moviemaking. He honed his onscreen trademarks, like a unique swagger and sparse, intentional speaking style, and mastered the physical side of moviemaking. Working principally in Westerns, Wayne needed to engage in rough and tumble onscreen tasks like fighting, roping and shooting, or riding a horse at full speed while a movie crew stood by, cameras whirling.

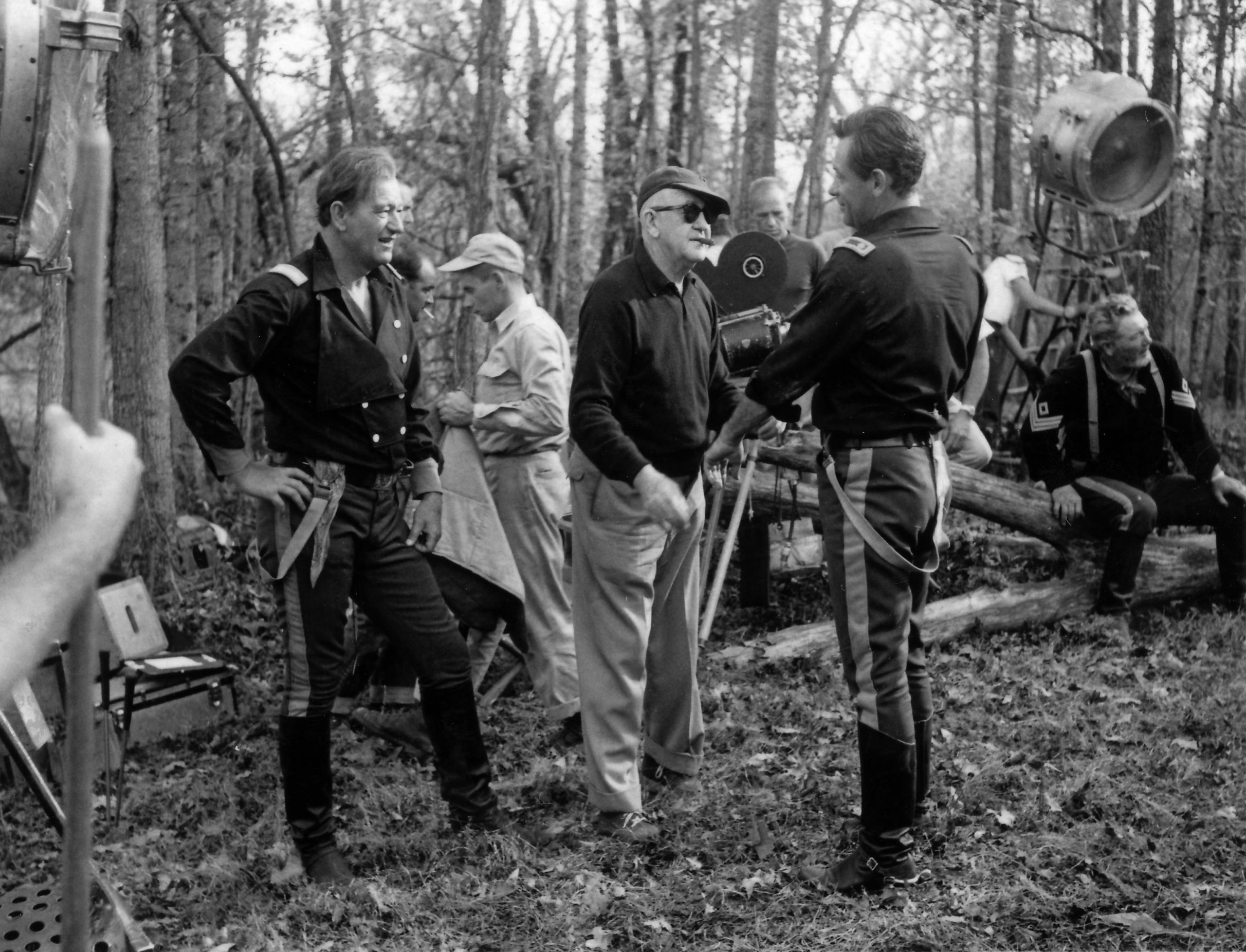

Few people know of the stunt prowess of Duke, who during this time, working as an all-around stage hand/extra/stuntman followed by a decade starring in B Westerns, trained and practiced unceasingly. And with the best in the business. Owing to a serendipity of time and place, Wayne was surrounded by some of the greatest practitioners in early Hollywood. Like John Ford, who Wayne studied at work, absorbing the older man’s filmmaking acumen. “The feeling I would come to have for scenes and just about anything else would come from standing behind him and watching him work,” Duke wrote in his unfinished autobiography of the man he would come to call ‘Pappy.’

When it came to filming action scenes, Wayne’s early mentors included stuntman Tom Bay (who Duke characterized as “one of the toughest men I ever met,”), as well as Allen Pomeroy and Eddie Parker, with whom Duke devised the no-contact punch. “It was easily twice as effective and realistic,” Wayne wrote of the innovation, still used on Hollywood sets today. Over his 50 year career, Wayne would work with leading stuntmen like Montie Montana, Dean Smith, and Chuck Robertson. The latter, a 6’4” cowboy nicknamed “Bad Chuck” by director John Ford, was Wayne’s stunt double for 30 years, starting with 1949’s The Fighting Kentuckian.

Most influential on young Wayne the stuntman was rodeo star and Academy Award winning stuntman Enos Edward “Yakima” Canutt, responsible for one of the most famous stunts in Hollywood history: The sequence in Stagecoach (1939) when he leaps onto galloping horses and, while being shot at by Wayne’s Ringo Kid, slides underneath the stagecoach to avoid being trampled. A legend in his craft who in later years would become a well-known director of action scenes, Canutt met Wayne in 1930, during Duke’s formative Hollywood days, and the two became close colleagues and friends. “With Yakima Canutt, they developed modern-day screen fighting, horse action and things like that,” recalls Duke’s son Patrick. “He [John Wayne] could handle a horse as well as any stuntman at the time.”

And Duke continued to do so throughout his 50 year career. He performed his own stunts on the bulk of his nearly 200 films, of which he was leading man in more than 140, eventually earning an honorary membership in the Stuntman’s Association. Duke’s dedication to his craft can be found in his insistence on doing his own stunts on the Mexican set of The Sons of Katie Elder (1965) mere months after his 1964 lung cancer surgery, and in Big Jake (1971), when he was in his 60s. It makes sense, after all, for an actor like Wayne who was shaped by the idea that being an actor meant much more than just reciting lines—that it meant entertaining his audience through full, vivid expression and often, riveting action scenes that Duke, imbued with a dedicated work ethic, could not help but perform himself.