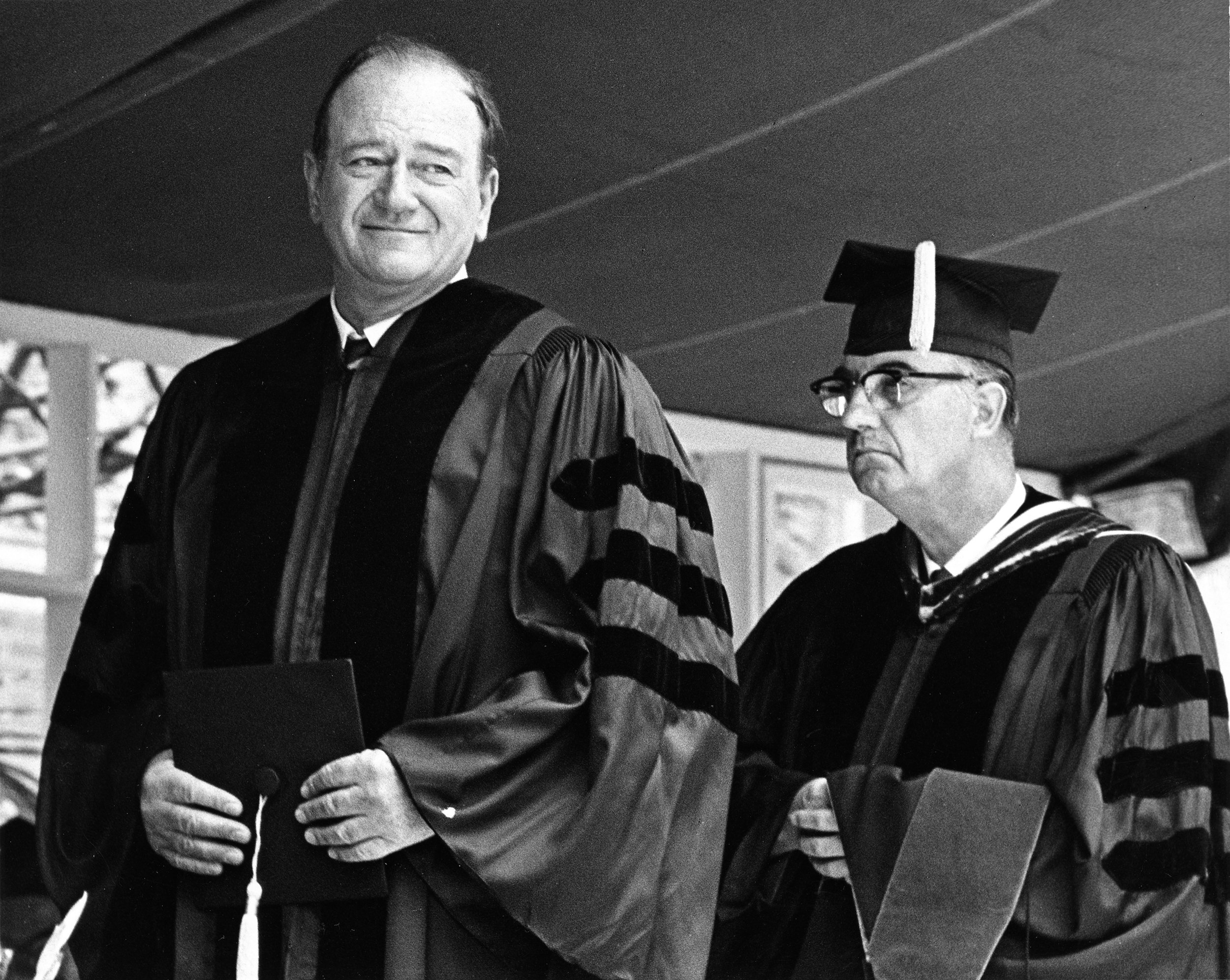

John Wayne (left) receiving his honorary doctorate degree from USC in 1968.

During these graduation days, we reflect on when the Duke did battle with the Harvard Lampooners—and how he won over the little liberals.

Written by Jenn Thornton

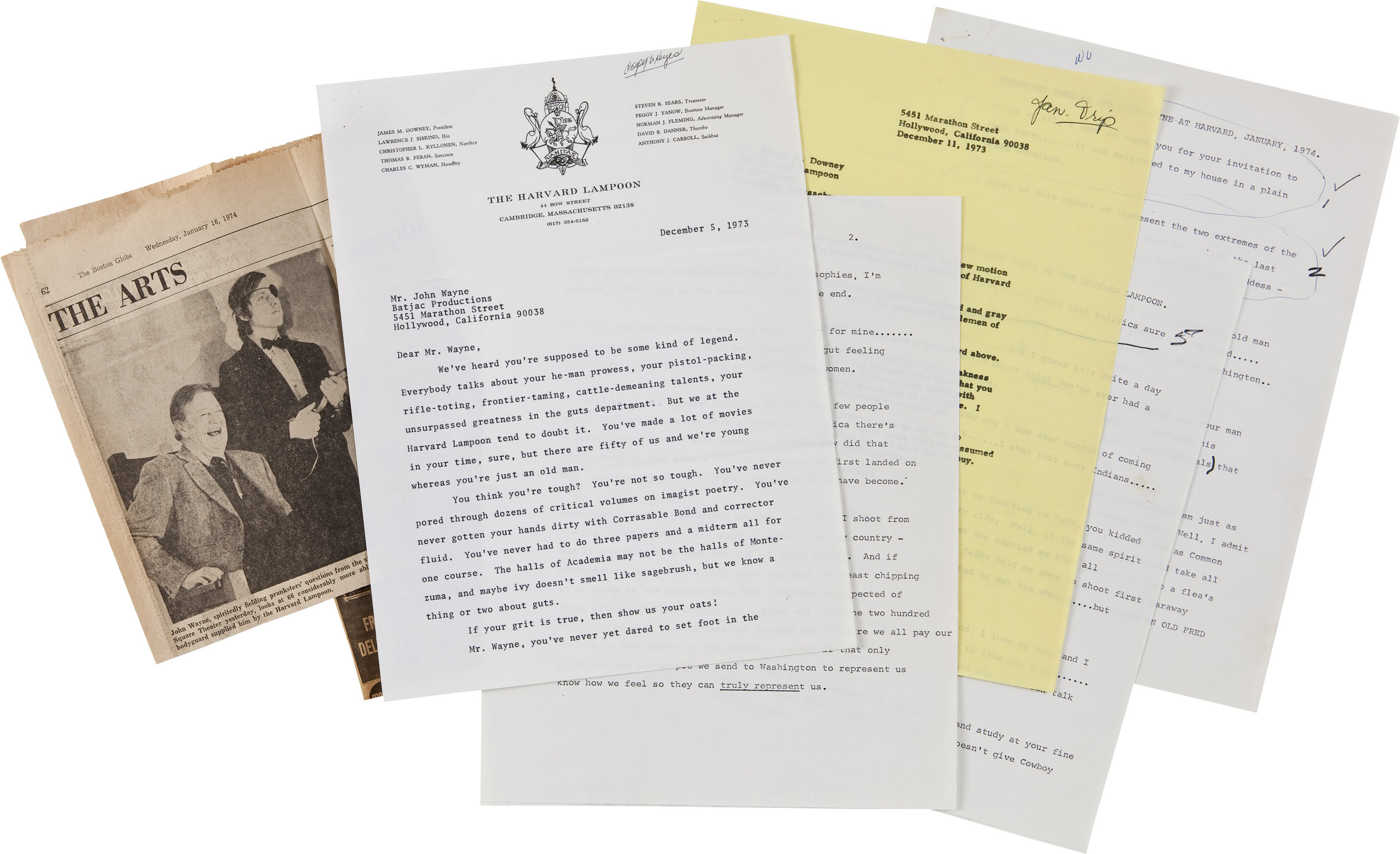

Like John Wayne, humor publication The Harvard Lampoon has a proud history. Perhaps in the hyper-political times of the 1960s and ‘70s, a clash of these two cultural tent poles was inevitable—the academic liberals versus the conservative film star. Representing the Lampooners, the group’s then president James Downey wrote a ridiculing letter to Wayne that roasted Hollywood’s biggest film star and invited the icon east to “have it out” with the wits of Cambridge. Rather than find the gesture impertinent, the good-humored, always game Wayne found himself amused at their brio and jumped at the opportunity, even as his mockers accused Wayne of being the “biggest fraud in history” and criticized his supposed toughness having never pored “through dozens of critical volumes of imagist poetry.”

So it was that on January 15, 1974, the bulwark of Republicanism came to the seat of liberalism at Harvard. Wayne had made a career of playing film characters in enemy territory, but Harvard Square was in a class by itself, known for its whip-smart student “radicals,” as they so often were judged in the estimation of Wayne’s generation. The actor arrived in trademark style—in an army reserve unit’s armored personnel carrier—and at the start of the event accepted an award for his nerve in daring to even appear (the Wayne camp might have told them that it’s called grit). The Lampooners then launched into a series of questions that Wayne took in stride, with arguably the only thing he had in common with the Lampooners—a sense of humor. According the New York Times, which covered the event, when a student asked Wayne if he had looked to President Nixon for suggestions for his films, the actor’s answer—“No, they’ve all been successful”—gave as good as he got.

In the end, a memory that Wayne recalled fondly, the actor did what he did best—played to the crowd, making them laugh. Nothing if not a good sport, the Duke proved he could take a joke and lob quite a few of his own. The whole thing evolved into a kind of mutual admiration society, showing that those with firm politics are never above a good ribbing. A lesson for Congress?

John Wayne (center) with son Patrick (left) at his graduation from LMU in 1961.