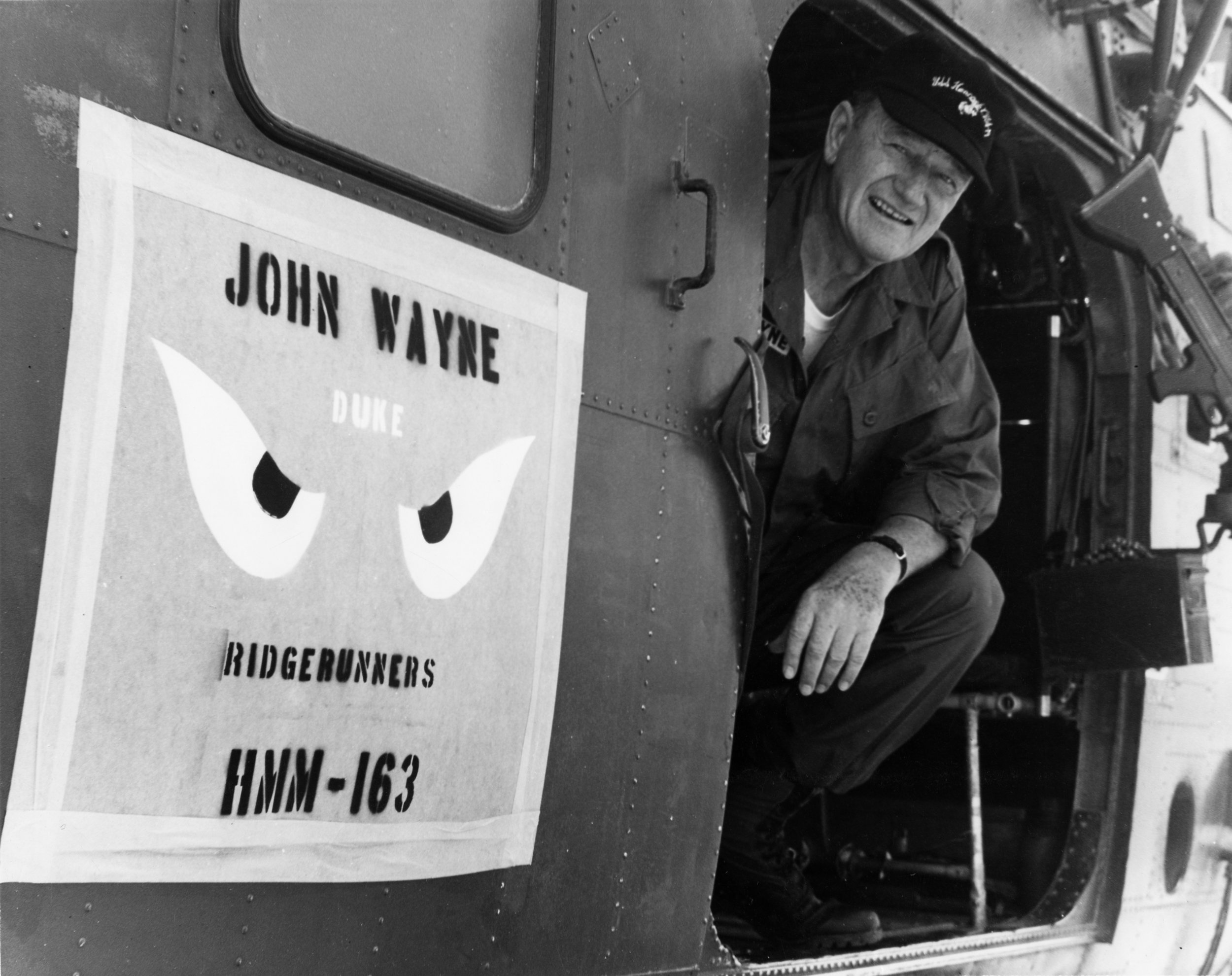

John Wayne aboard the Medium Lift Tiltrotor Squadron HMM-163 while visiting the troops in Vietnam in 1966. The aircraft was commandeered by the US Marine Corps helicopter squadron known as the “Ridge Runner’s”. The HMM-163 featured painted “Genie Eyes” after the “I Dream of Jeannie” TV show on the side of the helicopter. Photo courtesy of CPL. L. L. Atherton

Written by Michael Goldman

Last year marked the 50th anniversary of the release of one of John Wayne’s most controversial movies—The Green Berets. The 1968 movie was a passion project for Duke, one he sweated to make in the face of sometimes intense criticism, as he was determined to present a story that unabashedly justified and promoted the Vietnam War effort at a time in history when the tide was turning against that sentiment. After it came out, The Green Berets was generally poorly reviewed, but Duke never wavered from his convictions regarding his approach, which he felt the movie’s strong overall box-office performance validated. In fact, as a memento, he proudly kept a negative review of the film by critic Richard Schickel that appeared in LIFE magazine, over which he had written “six-and-a-half million in three weeks, thanks to left wing overkill” with a black Sharpie.

A half-century after the fact, it’s instructive to view Duke’s Green Berets experience from the point-of-view of how it impacted him on a personal and professional level. Regarding the issue of why Duke made the film against substantial obstacles, his son, Patrick Wayne, who co-starred in the movie, suggests that, at the end of the day, Duke was simply proud of the soldiers taking part in the war, and he wanted to back them. “We were in the middle of a contentious war, the country was polarized, it was very emotional,” Patrick says. “Dad took the position that these were American fighting men, he was proud of them, and he felt they should be portrayed in the best light. They were fighting for us, we sent them over there, so we should support them.”

Before, during, and after Duke made The Green Berets, he found himself passionately articulating what he was trying to do to those who wrote him. His archives are filled with letters discussing his intent, and why the project was so important to him. What is clear in reading these letters was his honest and unwavering motivation. “I hope [the picture] will spark a little patriotism among those lacking it in your generation,” he wrote in December of 1966 to a young high school student named Rodney Petersen in response to a request he could not meet due to his shooting schedule. And, in a letter to Brenda Normal of Cambridge, Mass, he explained: “I personally hoped the picture would give the thinking people of the United States a greater outlook on the present danger of Communism.”

But The Green Berets was important to Duke for other reasons, including the fact that it is one of only two films for which he received an official directing credit—the other was another passion project, The Alamo (1960). For The Green Berets, studio Warner Bros. insisted that Duke be supported by a more experienced director, so he chose Ray Kellogg, a second-unit director skilled in special effects and stunts. But make no mistake, the vision and result were all Duke’s, as was the painstaking work involved to acquire permissions, equipment, crew, advisors, and logistical help from the U.S. Government. To that end, Duke corresponded with Bill Moyers, then special assistant to President Johnson before he went on to become a famed television newsman, about setting up his original research tour of Vietnam in 1966, producing a script the Defense Department would approve, and all the production’s technical requirements. “We feel confident the finished script will be one that adheres closely to the thinking of President Johnson and the whole Administration regarding the role being played by US fighting men in Vietnam,” he wrote Moyers in February of 1966.

Along the way, in some quarters, Duke was accused of poaching U.S. military equipment and logistics at the expense of the war effort, which was not the case. He felt so strongly about that accusation that he took the time to write a lengthy reply letter to a Major McNerney of Huntington Beach, Calif., in July of 1969, to set the record straight: “We were allowed the use of four helicopters for a combined 85 hours, averaging about 20 hours a piece. And the use of them even for that limited time was at the convenience of the fliers who were fulfilling their normal need of time in the air in those copters. We paid for the gasoline in those instances. They had acres of howitzers and many tanks and personnel carriers at the base [in Fort Benning, Georgia, where most of the movie was shot], but we were allowed the use of one of their cannons for only an hour. We brought in our own jeeps and furnished uniforms for the personnel we used, which was only when the men were off duty. We brought in and bought and paid for our own ammunition and explosives.”

Still, with all the time, work, money, and critical backlash, the movie easily had its deepest impact on Duke in terms of the connection he formed with regular American fighting men during his 1966 Vietnam tour, corresponding with some for the rest of his life. Indeed, the depth and nature of Duke’s bond with American GI’s was discussed at length in a 2017 John Wayne Journal posting you can find here. As noted in that article, in August of 1966, Duke replied to a letter from Air Force Captain Robert S. Neilson, whom he had earlier met in the field. In that letter, he told Neilson, “I can’t tell you how proud I am to know each and every man I met in Vietnam. I wish I could let them know how thankful I am to them for their unswerving dedication.”