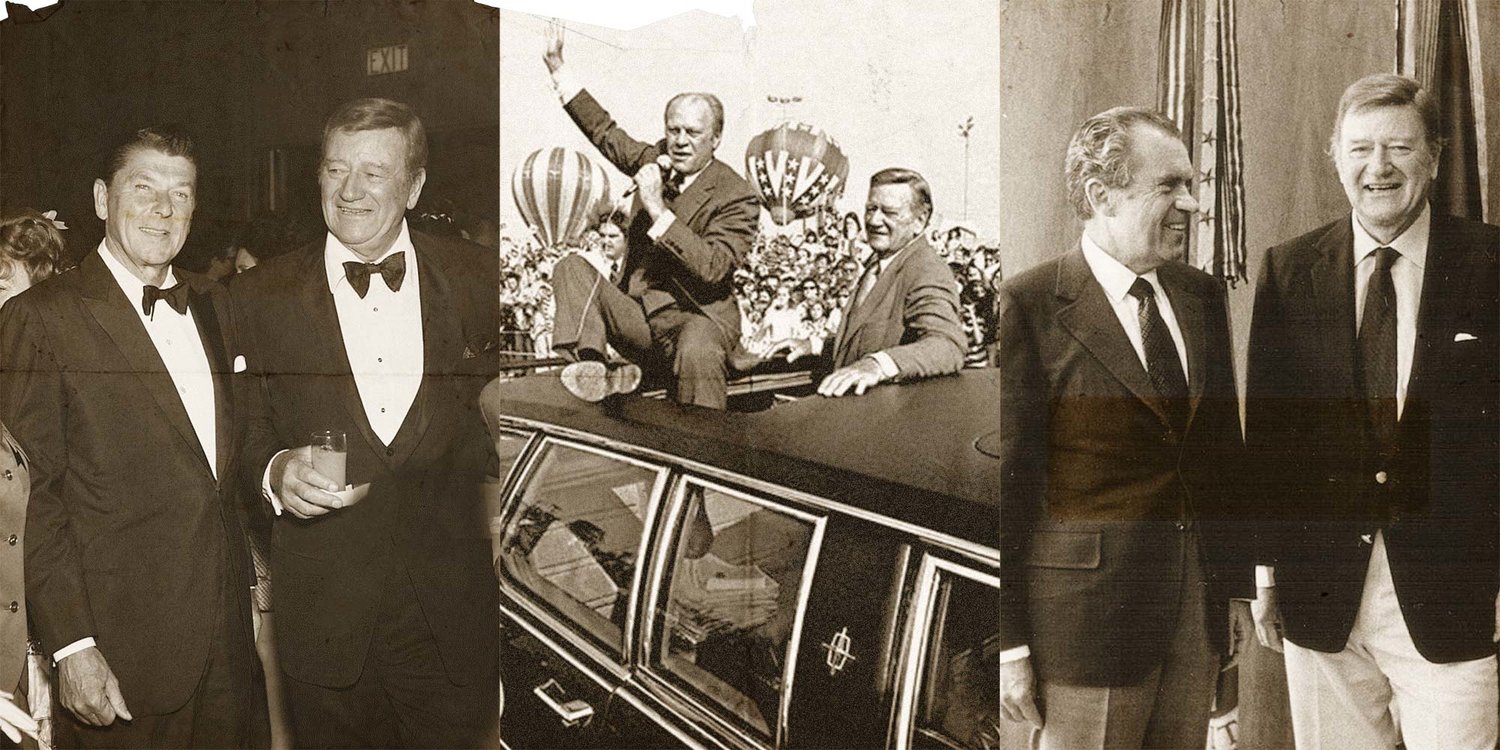

John Wayne with Ronald Reagan, Gerald Ford, and Richard Nixon. Photos courtesy of John Wayne Enterprises

Written by Michael Goldman

As we celebrate President’s Day, it’s reasonable to assume that John Wayne would appreciate the fact that the holiday commemorates the office of the president, not a single president’s life. Duke always expressed profound respect for the office, and enjoyed interactions and relationships with six Presidents—Dwight Eisenhower, John Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, and Ronald Reagan, with whom he was dear friends, though he died just before Reagan finally won the office.

Although Duke was a Conservative Republican, it would be a mistake to assume it was only Republican presidents whom he interacted with. Ironically, despite his ideological leanings, John Wayne was bipartisan when it came to the presidency itself—he respected and supported whomever held the job.

Duke was first lured into politics when he campaigned for Eisenhower. In a draft for a speech he gave on the eve of Eisenhower’s 1956 inauguration, Duke argued in plain-spoken fashion for the former war hero’s bona-fides as the next president based, simply, on his management skills as “a value that can’t be fooled around with.”

JFK was the first Democratic president to receive Duke’s famous congratulatory telegram sent to a president he didn’t vote for—“congratulations from the loyal opposition.” Lyndon B. Johnson and Carter would receive similar telegrams in the future. He often criticized Kennedy as too liberal, and yet, when Kennedy was tragically killed, Duke was as devastated as any average American.

In a letter Duke wrote to journalist Wayne Warga that exists in the John Wayne Archives, shortly after JFK’s death, Duke wrote of the pain that millions were feeling. “You didn’t have to be a Kennedy fan to be decimated by his assassination,” he said. “John Kennedy could have been so very good—he was just beginning to realize his responsibilities.”

Duke certainly didn’t vote for Lyndon Johnson. He supported his friend, Barry Goldwater, whom Johnson beat in a landslide in 1964. Still, despite Johnson’s victory, John Wayne was an unabashed supporter of the president’s Vietnam War policies, and worked closely with Johnson’s team to research and plan the 1968 Vietnam film he directed, Green Berets—a project Duke hoped would help lift flagging public support for the war fighters.

But Nixon was his closest personal friend to take the presidency during his lifetime. Their relationship began when Nixon was Eisenhower’s Vice President before seeking the presidency in 1960. A letter from Nixon to Duke after Nixon failed to beat Kennedy that year notes that it was “courageous” of John Wayne “to take sides” in political campaigns as a public figure, since doing so could potentially cost him fans.

After Nixon later became president, the two frequently corresponded, with Duke offering support and advice on many subjects. As Watergate dawned, Duke at first wrote Nixon encouraging notes, including a telegram in December 1973 telling him “don’t give up the ship.” Nixon replied that Duke shouldn’t “believe the rumors” that he would resign. But when Nixon did quit, Duke was clearly disappointed over Watergate. In a 1974 speech, he waxed philosophical that while Watergate itself was “a mess” and “positively, absolutely, dead wrong,” and “some men abused power,” he was pleased to see that “the system works.”

Earlier that year, Duke sent President Gerald Ford a letter thanking him for showing the courage to pardon Nixon, stating, “many thanks for your respect and feelings for the human dignity of Mr. Nixon. It is a lonely road. Here’s one you can count on—John Wayne.” That began a warm relationship with Ford, often writing him about topics as mundane as his concerns about a beef shortage in 1975, and headlining a tribute dinner to Ford shortly after he left office. He campaigned for Ford to win a full term, but when that didn’t happen, perhaps Duke’s most unlikely Presidential relationship commenced—his friendship with Democrat Jimmy Carter.

When Carter defeated Ford and received his “loyal opposition” telegram from Duke, he wrote back, pointing out he was a lifelong John Wayne fan and asking Duke to perform at his pre-inaugural ball. To the surprise of many, he agreed and gave a moving speech in which he declared, “I’m pleased to be present and accounted for in this capital of freedom to witness history as it happens—to watch a common man accept the uncommon responsibility he won fair and square by stating his case to the American people, not by bloodshed, beheadings and riots at the palace gates.”

Duke went on to regularly correspond with Carter, usually to critique his policies. Duke played a central role in lobbying Republican Senators to help ratify the Panama Canal Treaties favored by Carter, a topic Duke felt strongly about, having done business in Panama over the years.

When that decision upset his friend, Ronald Reagan, who was preparing to run against Carter and opposed the treaty, a series of letters in the John Wayne Archives illustrate the depth of the passion of both men on the issue, but also regarding their friendship. When Reagan finally wrote that he was concerned the dispute might harm their relationship, Duke wrote back and told him “you know damned well I have great affection for you and Nancy.”

John Wayne didn’t live to see Reagan beat Carter. It might have been awkward anyway, since he was fond of both of them. Just before taking on Reagan, Carter periodically visited John Wayne in the hospital during his dying days as he fought cancer, and would eventually eulogize him emotionally to the nation. Duke’s love for Reagan, meanwhile, was well documented—their relationship dated back to their Screen Actor’s Guild days. Perhaps Carter and Reagan would have found common ground with millions of others, or never pursued the office themselves, if Duke had run for president himself. Students at the University of Dallas pushed the idea to “Draft John Wayne” in 1964 under the reasoning that “we need a president who can act.”

But John Wayne, characteristically, had no interest when those students wrote him with the suggestion that year. He wrote them back and told them simply, “I’d rather be right than President.”

Michael Goldman wrote the 2013 award-winning book that examined letters and documents from John Wayne’s personal archive—John Wayne: The Genuine Article. Goldman has authored six books about major media-related topics, legends, and institutions, including co-authoring a textbook on filmmaking, an acclaimed coffee-table book on director Clint Eastwood’s filmmaking techniques called Clint Eastwood: Master Filmmaker at Work, an authoritative history of the USC School of Cinematic Arts, and more. He has also written for acclaimed film journals like American Cinematographer, CineMontage, Millimeter, Post magazine, Variety, and consumer publications like the LA Times, Orange County Register, Philadelphia Inquirer and others. Goldman podcasts interviews with filmmakers monthly at the Studio Daily site in a series called Podcasts from the Front Lines. You can learn more about his work at his Website—www.hollywood-scribe.com.