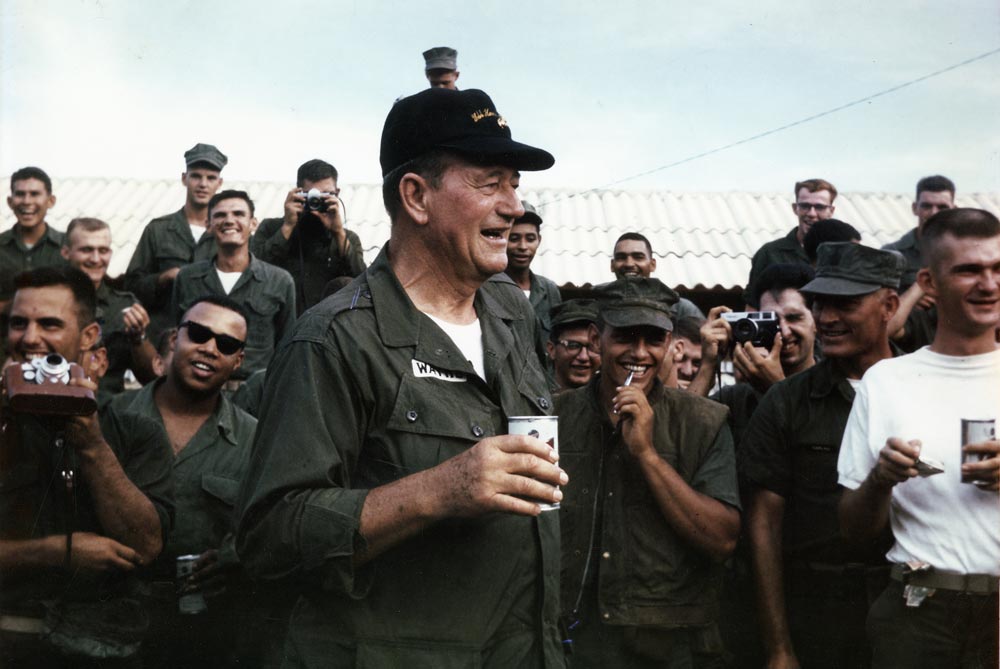

John Wayne visiting the troops in Vietnam in 1966. Photo courtesy of CPL. L. L. Atherton

Written by Michael Goldman

When John Wayne arrived in Vietnam in the summer of 1966 to visit American troops at the height of the Vietnam War as part of a tour co-sponsored by the USO’s Hollywood Overseas Committee and the U.S. Department of Defense, he was still in the early phases of developing the 1968 feature film he would eventually direct and star in, The Green Berets. Although one of his goals was ostensibly to do research for a film project that would eventually go on to become controversial for breaking with the era’s cinematic habit of disapproving the Vietnam War, it quickly became clear that the tour held more meaning for Duke beyond his movie project.

Despite the fact that he had visited troops before, during USO and base visits, it offered him an opportunity to interact extensively with regular soldiers in the field during an active conflict in an informal way he had never been able to do previously. Indeed, a large percentage of his tour was spent in close quarters with so-called “grunts” (a slang term for military infantrymen), regular GI’s laboring in the trenches without much glamour or attention coming their way until the legendary John Wayne suddenly showed up. As Duke told the press when asked why he went to Vietnam, he said he wanted to bring the grunts a bit of relief. “If nothing else, [his visit] gave the kids something else to write home about,” he told Stars and Stripes. “Life is so monotonous over there that they have nothing to put in their letters.” In another article in the Valley News newspaper, he explained, “I cannot sing or dance, but I certainly can talk to the kids.”

But what Duke didn’t anticipate was how profoundly his time with the troops would impact him, as documents in the John Wayne Archives illustrate. If you read his correspondence from that era, it’s clear that the 1966 Vietnam trip was a life-changing experience for him.

Indeed, two years later, on January 10, 1968, Duke received a letter from Sargent Gilbert Mumfort of the Fourth Infantry Division, whom he had met during his Vietnam tour. It wasn’t all that unusual—dozens of GI’s corresponded with John Wayne following his trip. Sometimes, they just wanted to be in touch; sometimes, they had a favor to ask or wanted an autographed picture, and so on. In Mumford’s case, he simply wanted to report about the most recent combat experiences of his unit, the Fighting Apache Raiders. Mumford wrote that he hoped Duke might find time to write back, because it would “raise our spirits.”

John Wayne did, in fact, write back, just nine days later, on January 19. “I don’t think the Apache Raiders need any words from me to lift their spirits and moral,” he wrote. “But tell them that the letter from you fellows raised mine.”

The John Wayne Archives are filled with such handwritten letters and photos from GI’s in the field from that period, and copies of notes back from John Wayne. Sometimes, soldiers would just send Duke letters of appreciation for his visit, such as the undated letter from nine members of a rifle platoon calling themselves “Men of the 1st Squad.” That group sent him a simple note, thanking him “for what you have done for the men in Vietnam,” and calling him “one of us in the fight for freedom.”

Meanwhile, Duke always tried to honor reasonable requests, sign autographs, share anecdotes, and on at least one occasion, he sent cases of strawberry preserves from Knott’s Berry Farm to an entire unit. The gift giving went both ways, of course. On June 23, 1966, several field commanders signed a note to Duke in-country to commemorate a gift they had presented him, taken in furious combat a few days earlier—a Chinese Chicom Carbine Rifle, pulled out of a large cache of weapons from a North Vietnamese ship on June 20.

“Please accept the weapon as a token of our appreciation for your visit today and the many hours of enjoyment you have given us all at the cinema,” the commanders wrote.

Of course, the most famous gift Duke was given in Vietnam was the silver friendship bracelet presented by a Montagnard Strike Force unit, made up of indigenous Vietnamese soldiers. The bracelet was bent to fit his wrist, and he wore it for the rest of his life.

Naturally, Duke couldn’t accommodate every GI request. During the trip, he told some soldiers about plans to make the Green Berets, and a few of them thought that perhaps they could help. Captain John Welker of the 5th Special Forces Group was one of them, writing Duke on July 28, 1966, to reminisce about his time with Welker’s unit a month earlier. Captain Welker then took the liberty of “nominating myself for the position” of technical adviser on Green Berets. Duke wrote him back on August 10, pointing out that he had to get Pentagon approval for any Armed Forces advisor, and couldn’t even make a request until his script was finished. But, in typical John Wayne fashion, not wanting to lead the soldier along, Duke added a postscript in which he stated bluntly, “you’ll have to stand in line for that job. Everybody has asked for it.”

However, John Wayne was ever mindful that the grunts weren’t participating in a movie, and that their effort and sacrifice went far beyond what most people could possibly comprehend. Such understanding was never far from his thoughts, but if he needed a reminder, he got one when he received a letter in February of 1968 from a Mr. and Mrs. Bruce Carpenter of Youngstown, Ohio, informing him that their son, a Special Forces member whom Duke had met in Vietnam two years earlier, had been killed in action.

John Wayne wrote them an aching letter of condolence in reply.

“It’s most difficult to find the right words (if there are any) of sympathy and comfort,” he wrote. “But, as one parent to another, I am sure the fact that your son, in these days of irresponsibility on the part of so many young people, voluntarily joined the Special Forces, volunteered to do what he did, and did it very well apparently, must give you great pride. The weeks and months I spent in Vietnam and at Fort Benning filming the picture, The Green Berets, and working with many Green Beret trainees and veterans, brought me very close to them. They, like your son, are men whom all of us should be very proud.”

Michael Goldman wrote the 2013 award-winning book that examined letters and documents from John Wayne’s personal archive—John Wayne: The Genuine Article. Goldman has authored six books about major media-related topics, legends, and institutions, including co-authoring a textbook on filmmaking, an acclaimed coffee-table book on director Clint Eastwood’s filmmaking techniques called Clint Eastwood: Master Filmmaker at Work, an authoritative history of the USC School of Cinematic Arts, and more. He has also written for acclaimed film journals like American Cinematographer, CineMontage, Millimeter, Post magazine, Variety, and consumer publications like the LA Times, Orange County Register, Philadelphia Inquirer and others. Goldman podcasts interviews with filmmakers monthly at the Studio Daily site in a series called Podcasts from the Front Lines. You can learn more about his work at his Website—www.hollywood-scribe.com.