Mary St. John in John Wayne’s home in Encino, California. Photo courtesy of John Wayne Enterprises

Written by Michael Goldman

There are many candidates to claim the spot of John Wayne’s closest confidante. As previously discussed in this space, his buddies John Ford and Ward Bond come to mind, as does legendary actress Maureen O’Hara. Less discussed, but only because she avoided the limelight, would be Mary St. John, his friend and personal secretary of almost 30 years. In many ways, she fits the bill better than any of them.

Mary first met Duke when she was running the secretarial pool at Republic Pictures in 1937, and then eventually left the studio when Duke literally stormed out during a dispute with studio boss Herb Yates. According to various accounts, Mary helped Duke pack his things, prompting Yates to ask where her loyalties lay. “With Wayne,” she replied as she walked out the door with him. She proceeded to run Duke’s office, intimately involved in his personal and professional affairs, until her retirement in 1975.

Pilar Wayne and Mary St. John. Photo courtesy of John Wayne Enterprises

But Mary St. John was far more than a personal assistant—she was one of John Wayne’s most loyal friends. She faithfully wrote him wherever he was in the world while filming pictures to update him not only on office affairs, but also about his family, wife, and children, as well as her own life. She was the one who let him know his family was OK when a fire struck his house in 1958 while he was filming Barbarian and the Geisha in Japan. She wrangled the press, hired teams of secretaries to handle the reams of mail pouring into his home daily, updated him on his mother’s health, holidays he was missing, his children’s accomplishments, and frankly lectured him when she felt a business associate was attempting to take advantage of him. She attended parties with Duke, expressed fears for his safety on faraway locations, occasionally moved into his house when he was traveling to care for his family, and she was right there during his cancer battle in 1962 and to help sort out financial setbacks.

In other words, Mary St. John was dedicated not only to her job—she was dedicated to Duke himself and, by extension, his entire family. Indeed, all the Wayne family members who were around during her time in John Wayne’s orbit have particularly fond memories of Mary. Duke’s oldest surviving son, Patrick Wayne, for example, emphasized that “Mary was as dedicated to [Duke] as if they were related.” Pilar Wayne, John Wayne’s third wife and mother of three of his children, reminded that Mary St. John was her only attendant at her wedding to Duke in 1954 in Hawaii. She also reminded that Mary’s relationship during that era was, in fact, with the whole family. “To me, she was more like my mother,” Pilar said.

A visitor to the John Wayne archives can contextualize these statements by reading letters Mary St. John wrote Duke over the years. A series of weekly letters, penned by Mary between October 11, 1957, and January 24, 1958, while Duke was filming in Japan and Mary was watching home and office for him illustrates the intimacy of their bond. Most feature a sign-off varying from “love” to “much love” to “love always.” Some are addressed to both Duke and Pilar, and contain as much personal discussion as office talk.

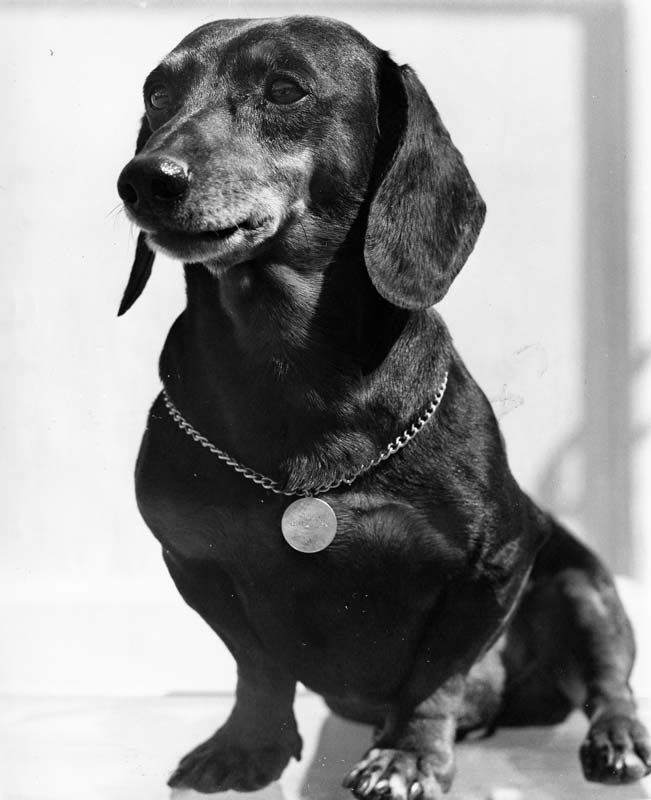

The Wayne family dachshund “Blackie.” Photo courtesy of John Wayne Enterprises

On Nov. 26, she happily reported that little daughter Aissa had “learned to say some colors like pink and green”; on Dec. 27, she thanked Duke and Pilar for sending her a Kimono from Japan and “for the lovely handbag and generous check that came my way;” on Dec. 11, she told Duke she was “in the dumps” because her “little dog ‘Punch’ ” had died from an intestinal infection, and she swore she would never get another dog. Then, on January 15, she told him the details of the fire at his house, and in a legendary tale, how the family dog, Blackie, woke Pilar and alerted her to get out of the house, averting a tragedy.

“Thank God for little Blackie, as Pilar was sound asleep and had been for several hours,” she wrote. “We sure got that little dog a big, beautiful hunk of roast beef and all the coffee he wanted.”

But other letters involved heartfelt declarations of empathy for the burdens Duke had to bear. In February of 1957, she wrote to say she had “always approached your problems in a very personal way—as if they were my problems too. … My primary purpose in this job is to help solve as many of the problems that confront you as it is possible for me to solve.” That theme continued at the end of that year when, on Dec. 2, 1957, she wrote about how vexing it was for her to try to constantly evaluate who really needed his help compared to those who were trying to take advantage. “There seems to be very little I can do, except to be on the receiving end for all complaints that people want to write or cable you about (but seldom do),” she wrote. “They come in and talk to me about their beefs; I listen and try to figure out where the trouble really lies.” she explained.

Mary St. John finally retired in 1975, and Duke threw her a farewell bash at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel. But she returned “to help out,” according to a note she wrote in Duke’s date book, on April 18, 1979, when he was admitted to the hospital with pneumonia as his health declined, just a couple months before his death. Then, according to what she told authors James S. Olson and Randy Roberts of “John Wayne: American,” she was among the last people to see John Wayne alive—visiting privately with him just three days before he passed away.

John Wayne and Mary St. John in Hawaii for Wayne’s Wedding to Pilar Palette in 1954. Photo courtesy of John Wayne Enterprises

According to their book’s acknowledgments, Olson and Roberts tracked Mary St. John down in Kansas City where she had retired, and talked her into doing an extended interview for their book. They said the interview began at 9 a.m. one morning and didn’t end until 1 a.m. the next, and that Mary remained a source to them throughout their project after that. As near as I could tell, the only other journalist to interview her extensively about her time with Duke was Wayne Warga, the former L.A. Times and Life writer and book author who attempted to work with Duke on his biography in the mid 1970s before Duke called the project off, as I documented in my book.

In handwritten notes that are part of a collection of his papers at the USC Doheny Library, Warga quotes St. John as insisting that Duke was “always involved with people and a sucker for the underdog.” Knowing him so well, she also explained Duke’s penchant for raising his voice that, St. John insisted, was often misinterpreted by those who did not know him well.

“People say he yells,” she told Warga. “What he does do, especially with me, is recreate his experiences of the day. He doesn’t tell his experiences as other people do. He relives them, and he puts all of himself into his dictation, peering at me over his glasses to see if got the full impact.”