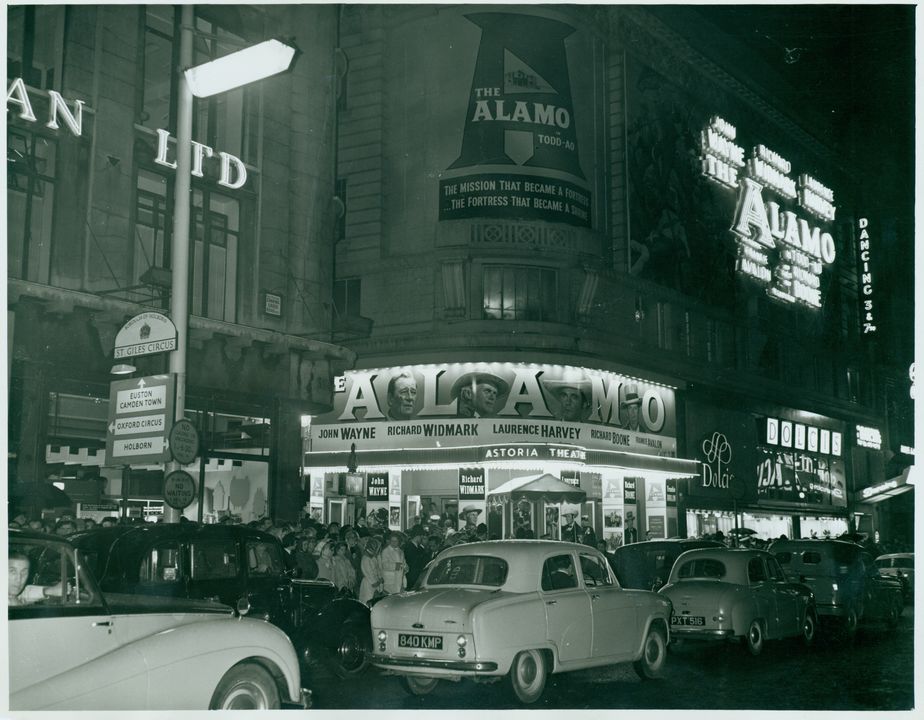

Fans line up outside the royal premier of The Alamo (1960) in London, England. Photo courtesy of Charles Kieskalt.

Good thing the man with the reins to The Alamo was John Wayne.

Written by Jenn Thornton

Good thing the man with the reins to The Alamo was John Wayne. His full directorial debut, which stormed into theaters in all its epic glory in 1960—backed by his desire, his dollars, and his resolve—took two decades to get off the ground, and only did so with Duke’s doggedness to get the thing done.

With the amount of clout Wayne had in Hollywood, it’s likely he could have directed anything, a musical even, but he banked on what was to him a deeply personal and important story. The Alamo was, says Jason Apuzzo, Ph.D., a graduate of USC School of Cinematic Arts, a “statement of idealism”and Wayne’s “passion project.” Shot after WWII, during the Cold War, The Alamoallowed Wayne to say something about the nation’s tenacity. “I think Wayne wanted to go back to America’s early frontier days to dramatize a similar struggle,” notes Apuzzo.

Behind the scenes, the battle was for financing. Duke signed up to play Davy Crockett, a precondition from investors. Appearing in the film wasn’t his plan, but “once he knew that the only way to finance the film was for him to star in it, he then set out to craft the role in a way that suited his persona,” says Apuzzo. “Honestly, though, I can’t think of anyone better suited to portraying a larger-than-life folk hero like Crockett than John Wayne.

A scene from The Alamo (1960) featuring Richard Widmark, John Wayne, and Laurence Harvey. Photo courtesy of Batjac Productions.

There was little to teach Wayne—he knew film production, he understood storytelling. A top-draw for decades, he started out as a prop hand at Fox, did a great deal of stunt work, and had success as a producer. He’d also at various times in his career spot-directed (filling in for Michael Curtiz on The Comancheros when the auteur fell ill, for example). “The Alamo is unique in being a film in which we get to see him wear all of those hats—actor, director and producer—with everything happening on a very large scale,” explains Apuzzo. No doubt Wayne also benefitted from having worked with some of the biggest auteurs in the business—notably Howard Hawks and John Ford, a de facto force in Duke’s life and a presence on set of The Alamo, a situation Wayne diplomatically managed.

As a director, The Alamo makes one look at Wayne more broadly as an artist and director. “I do think it was a role he was comfortable in, and he likely would have been even more comfortable in were it not for the fact that he also had to star in the films—and sometimes produce them,” says Apuzzo, adding that “it’s possible he would’ve ultimately transitioned into a career similar to Clint Eastwood’s—in terms of retiring from acting, while staying active as a director.” One looks at the possibility very seriously when appraising The Alamo, which did well financially (though not enough to recoup Wayne’s robust personal investment in the film), garnered generally positive reviews and received six Academy Awards nominations, including one for Best Picture. It won for Best Sound. Most significant was the vindication for Wayne.

“With respect to John Wayne’s career,” Apuzzo concludes that The Alamo was “is probably the best overall statement about what he wanted his life and career to stand for I think it’s one of his best films—in large part because of its epic scale, rousing idealism and big emotions. Everything about the film is large-scale and ambitious, including its heart-on-the-sleeve championing of American freedom.” Not unlike John Wayne himself.