Highlights of John Wayne’s personal collection—including Kachina dolls and rare Native American imagery—are on show at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

Written by Constance Dunn

Derived from the Hopi term “kachi,” meaning “spirit” or “life,” Kachina dolls were given to Hopi children as teaching objects, with each doll highlighting a specific deity. “They represent an aspect of the supernatural realm in Hopi,” explains Eric Singleton, Ph.D. Curator of Ethnology at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, Singleton adds: “Historically, Kachina dolls could have actually taken on a deity. Later on they became a little bit more of a tourist trade item.” Typically constructed from the root of a Cottonwood tree, Kachina dolls were first carved, then decorated—perhaps with feathers, fur and other fabrics—and painted. Head to the Western Performers Gallery at the Museum and one will currently find about seven of these historical objects on display—a portion of the 81 Kachina dolls bequeathed by the estate of John Wayne to the Museum in 1979.

The Museum’s Duke-dedicated display case pays tribute to Wayne as both a performer and collector: There are his costumes from True Grit (1969) and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), along with a trio of grand Buddhist Thai statues that, like the rest of Wayne’s collection, are shown on a rotating basis. Perhaps most incredible are the volumes and portfolios of Edward S. Curtis on display, also part of Wayne’s personal collection gifted to the Museum. It was a quest of Curtis, an American photographer and ethnologist, to document the American West and Native American people in the early 20th century—a time of fundamental transformation in North America. “His goal was to capture a vanishing Indian concept,” explains Singleton. “He is photographing a change in society and a change in culture.”

Curtis’s extraordinary works were gathered in his multi-volume opus, The North American Indian, containing 20 volumes of illustrations and text, along with supplementary portfolios containing large reproductions of his original photogravures. The first volume of the series was published in 1907, and for 23 years onward until 1930, subsequent volumes were produced. While Curtis’s images are arresting, Singleton points to his ethnography work as being a particularly vital part of documenting and learning about Native American cultures, including Curtis’s recording of real-time situations and behaviors while living amongst various tribes. “Inside the volumes he does a pretty good job of laying out Arikara and Pawnee and other cultural aspects to communities,” Singleton remarks.

“Inside the volumes he does a pretty good job of laying out Arikara and Pawnee and other cultural aspects to communities.”

— Eric Singleton

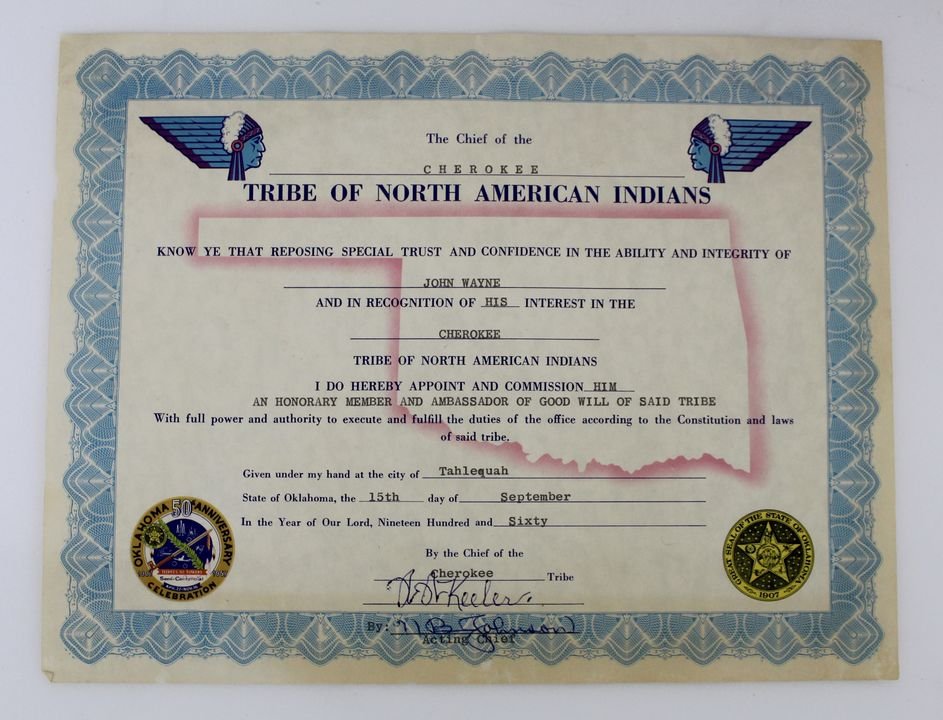

In the end, only about 200 completed sets of The North American Indian were ever published, making this a particularly rare and treasured part of Wayne’s gift to the Museum. “The fact that you have that limited amount, and one is here, given by John Wayne, is pretty remarkable,” points out Singleton. “I think it’s one of the best things he gave us.” As a performer, Wayne’s films are offered as cultural artifacts, though of a different time and place. The Museum, via their evening series A Date with The Duke, screens curated John Wayne titles during dinner events. But as a collector, Wayne’s gift to the Museum showcases the actor’s depth of curiosity and engagement with culture and history—of the American West and beyond. So much that in 1960 famed Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, W. W. Keeler, appointed Wayne as an Honorary Member and Ambassador of Goodwill of the Tribe. This certificate, along with a trove of Wayne’s other personal artifacts, can be viewed at John Wayne: An American Experience. The expansive exhibit, measuring over 10,000 square feet, is located at the Fort Worth Stockyards, and presents a multi-faceted view of The Duke—as both public figure and individual. “I also think it speaks to humanity’s complexity,” says Singleton of Wayne’s 1979 gift to the Museum: “This guy is known for being a John Ford cowboy, and at the same time he collected a lot of Native American material.”

“The fact that you have a limited amount, and one is here, given by John Wayne, is pretty remarkable.”

Photographs courtesy of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum (unless otherwise noted)